Paula Rego: The Forgotten

19 November 2021–12 February 2022

Tuesday–Saturday: 10am–6pm

No booking is required when visiting the exhibition

Victoria Miro is delighted to present The Forgotten, a major exhibition by Paula Rego. Held across the entirety of its Wharf Road spaces, the gallery’s first solo exhibition by the artist brings together significant individual works and important series, many rarely shown, drawn principally from the past 20 years.

Celebrated as a peerless storyteller, Paula Rego has often brought immense psychological insight and imaginative power to the stories that we try to suppress or tell ourselves only in private. Testament to a career spent exploring these hidden narratives and their associated stigmas, The Forgotten encircles themes and subjects that are often masked or concealed – out of politeness or embarrassment – such as mental illness and old age.

The Forgotten a new book is available now, illustrated with all works in the exhibition and featuring a text by Deborah Levy. Click here to purchase.

La Marafona

Pastel on paper on aluminium

187 x 135 cm

73 5/8 x 53 1/8 in

Paula Rego, La Marafona, 2005

More info‘These are episodes from Paula’s life growing up in Portugal and are separate stories of her relationship with her dad.’ — Nick Willing

The exhibition includes works inspired by episodes from the artist’s childhood in Portugal, including the large-scale La Marafona, 2005, a tender portrayal that refers to the burden of her beloved father’s depression. Rego considers her own depression to have been inherited from her father and her identification with his suffering – and its legacy – is explored elsewhere in the exhibition.

Speaking about this work, the artist’s son, Nick Willing, says, ‘This is a family picture. Paula’s mum is behind her dad, holding him with her hands on his shoulders. And Paula has her head leaning on his shoulder. He’s wearing a crown of thorns because that’s Paula’s way of showing that he suffered from depression. La Marafona is also Paula. Really it is about how she identified with him because she also inherited depression.’

Reading the Divine Comedy by Dante

Pastel on paper on aluminium

180 x 120 cm

70 7/8 x 47 1/4 in

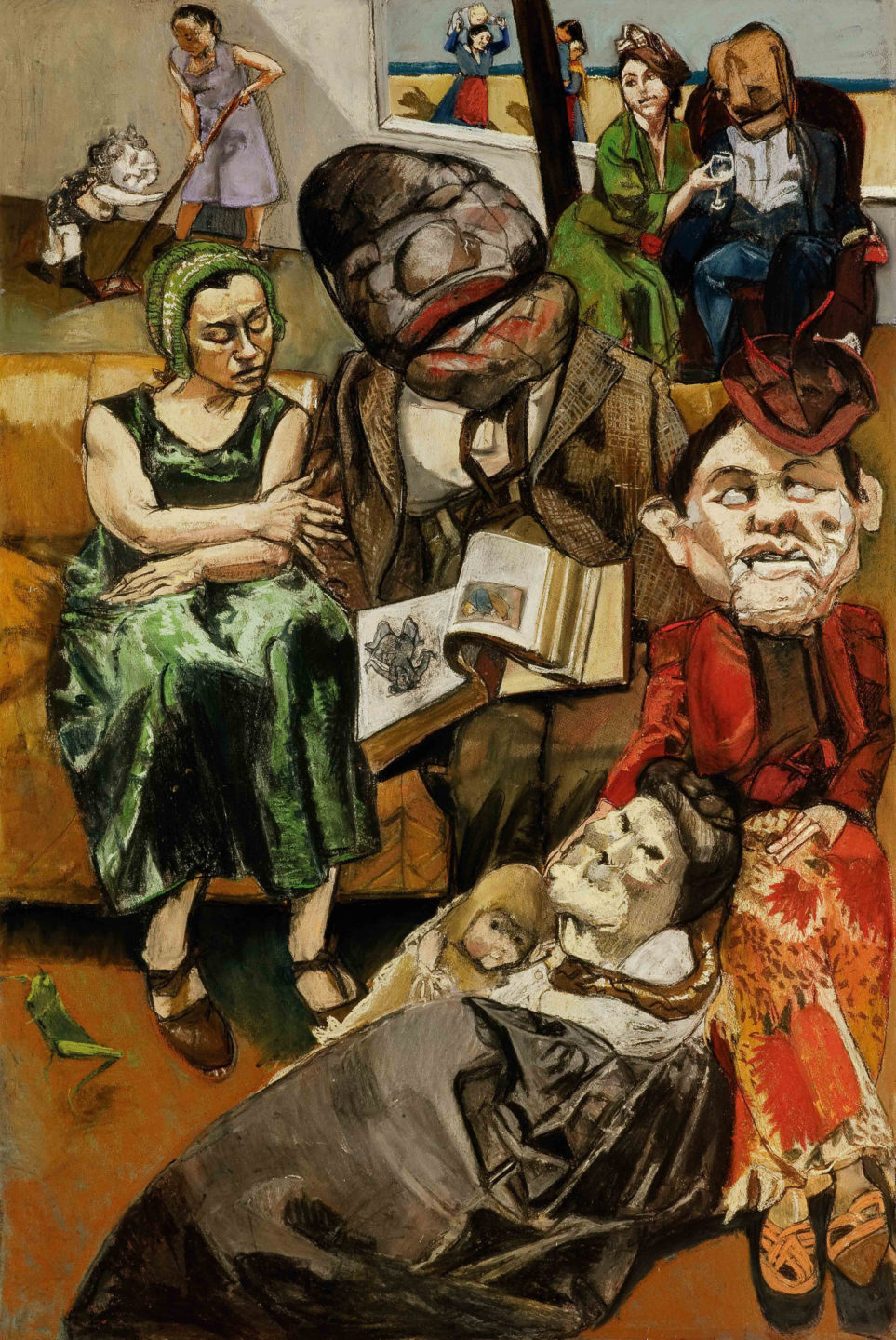

Paula Rego, Reading the Divine Comedy by Dante, 2005

More info‘This morphing of realism and surrealism gives equal status to the ordinary and the extraordinary, in which, as ever, the artist is also working with fragments of memory.’ — Deborah Levy

The book being read in this picture is a limited edition of Dante’s Divine Comedy with etchings by Gustave Doré. It was a book that Rego’s grandfather bought in 1890 and has been in the family ever since. During her childhood, Rego and her father would look at the book together. She sets the scene in Estoril, its beach glimpsed through a window, with narratives within the picture suggesting episodes by turns domestic and uncanny. Writing in the accompanying publication, Deborah Levy notes that ‘This morphing of realism and surrealism gives equal status to the ordinary and the extraordinary, in which, as ever, the artist is also working with fragments of memory.’

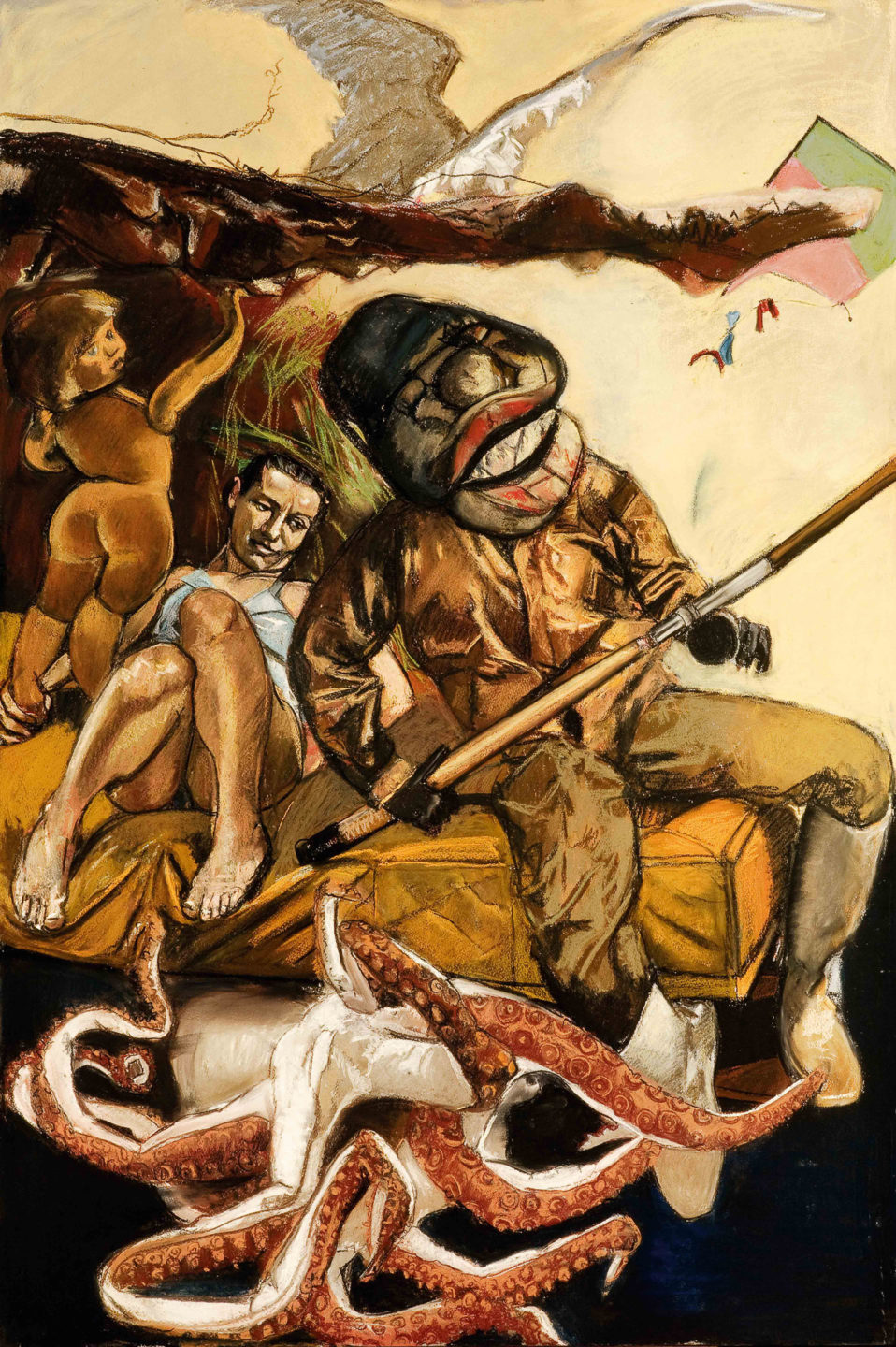

The Fisherman

Pastel on paper on aluminium

180 x 120 cm

70 7/8 x 47 1/4 in

Paula Rego, The Fisherman, 2005

More infoThe Fisherman is the third work on view that relates to Rego’s father and scenes from her early life. In this work, which is based on a specific episode from the artist’s childhood, a figure – the artist’s father – captures a giant octopus. The surrounding space appears to occupy both interior and exterior worlds and, as a result, seems to point to psychological as much as physical surfacing – the drawing up of thoughts, memories and emotions.

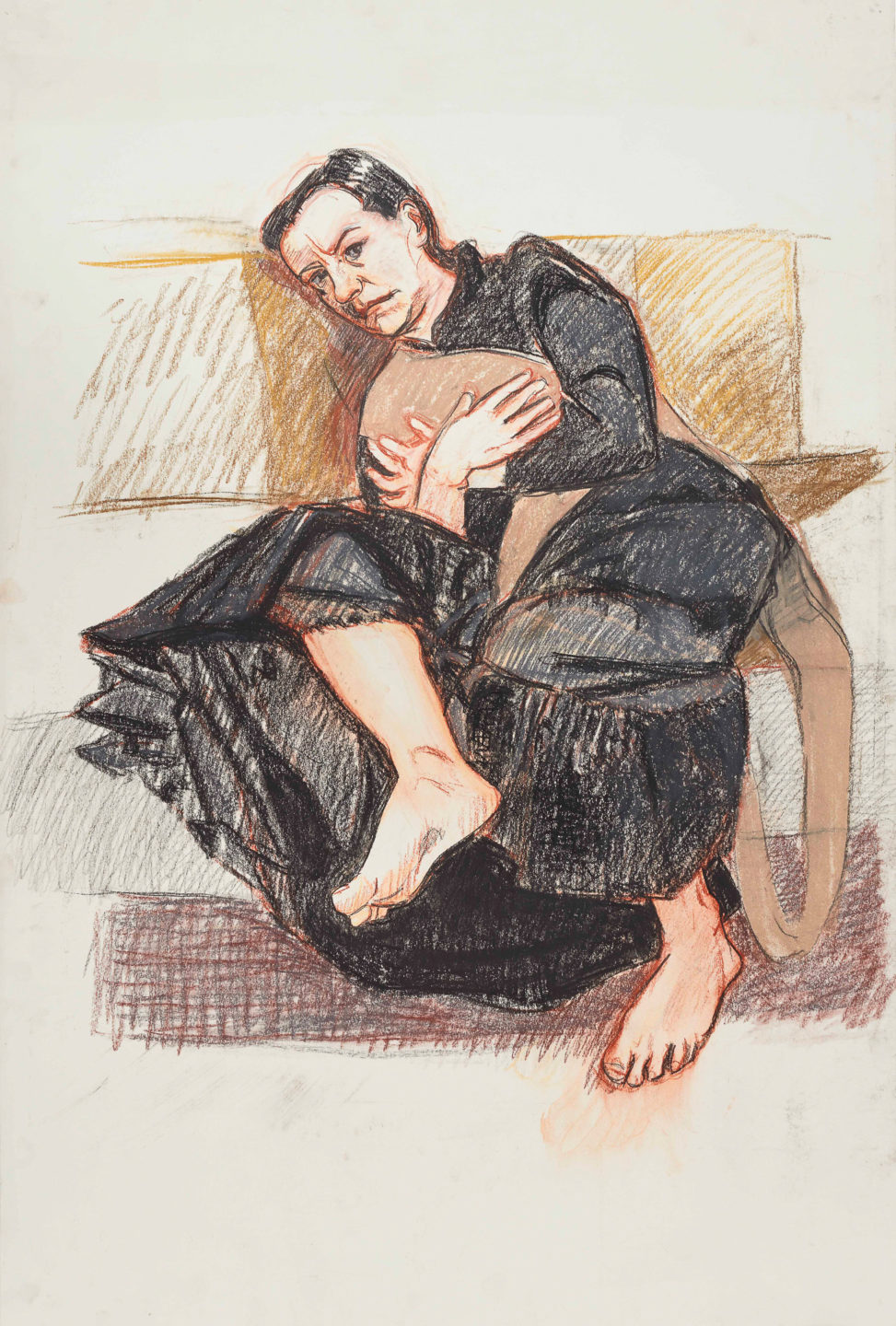

Works on mylar, 2000

Wax crayon and watercolour on mylar

80.5 x 60 cm

33 5/8 x 23 5/8 in

Paula Rego, Nursing, 2000

More info

Wax crayon and watercolour on mylar

80.5 x 61 cm

31 3/4 x 24 1/8 in

Paula Rego, Convulsion IV, 2000

More info

Wax crayon and watercolour on mylar

80 x 58 cm

31 1/2 x 22 7/8 in

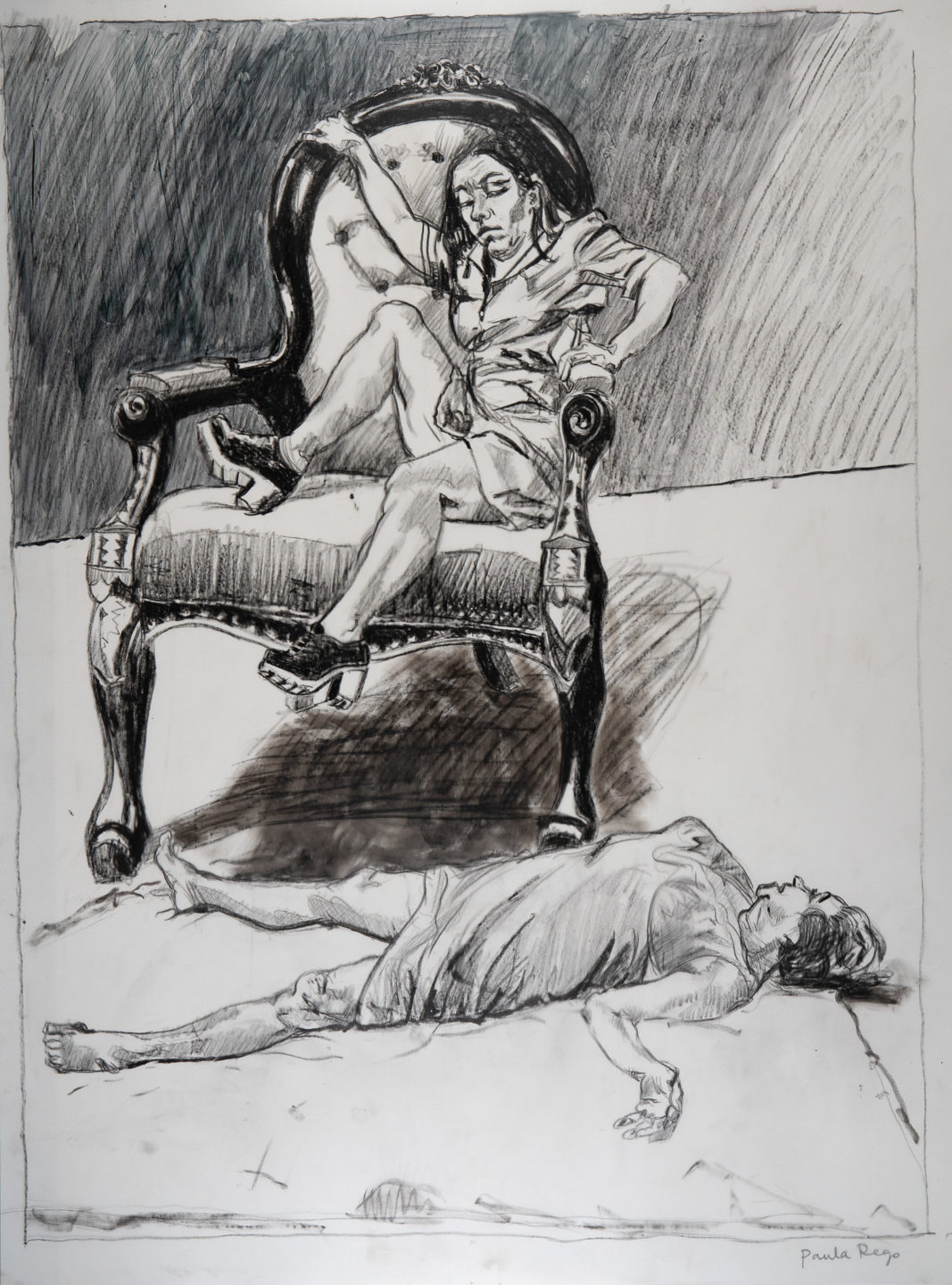

Paula Rego, Girl on a Large Armchair, 2000

More infoThe relationship between daughters and their mothers, a recurring theme in Rego’s art, is prevalent in a number of works in the exhibition. Nursing, 2000, is a large-scale monochrome work that delivers successive waves of shock: bodily transformation wrought by age and the apparent ambivalence of the carer. In Convulsion IV, a woman recoils in apparent disdain from the figure of an older woman who seems to writhe on the ground as if suffering a seizure. Each work features an oversized armchair that, skewing a sense of scale, creates a hallucinatory, almost Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland atmosphere to images that, equally, distort accepted notions of familial care and the roles of adult and child.

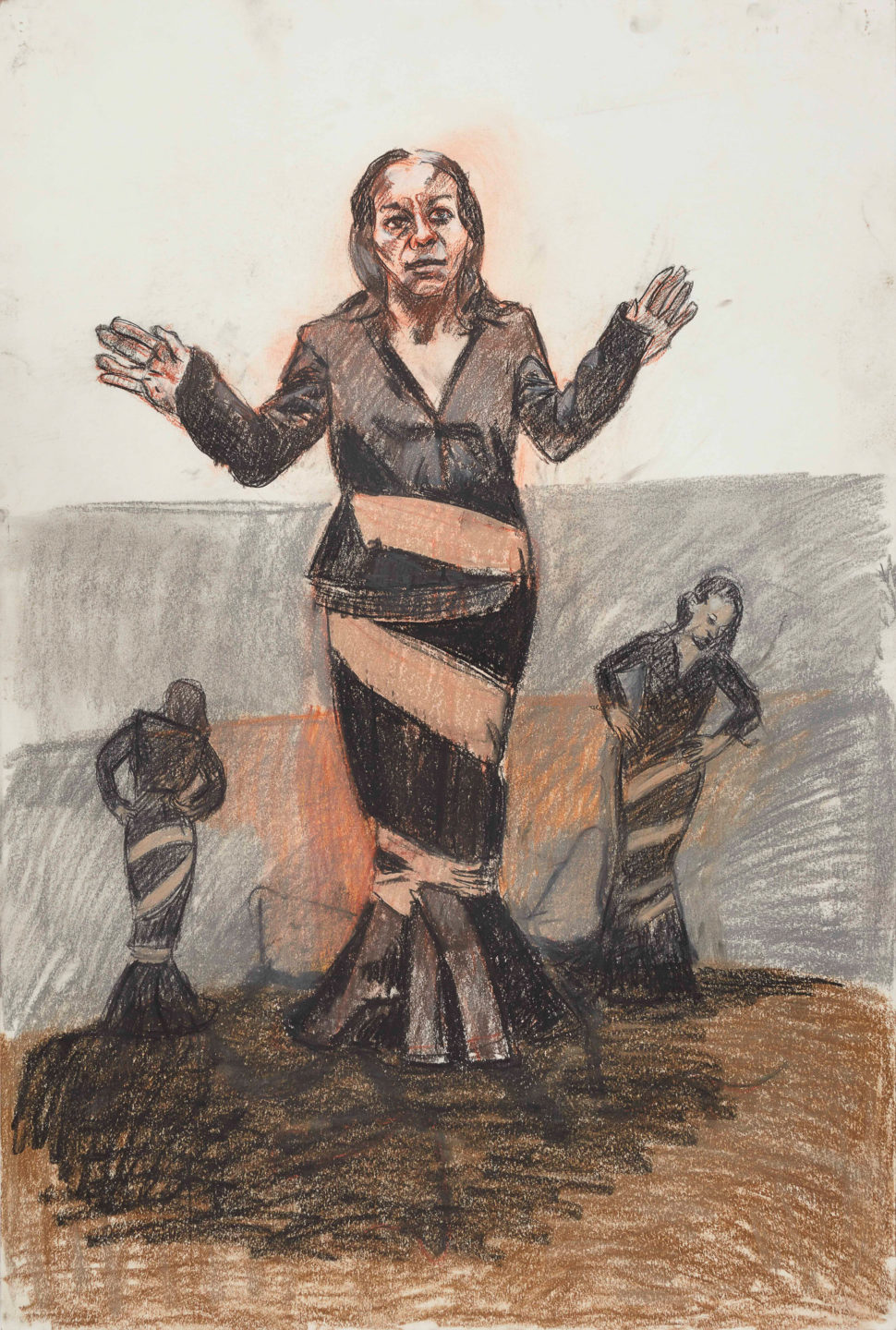

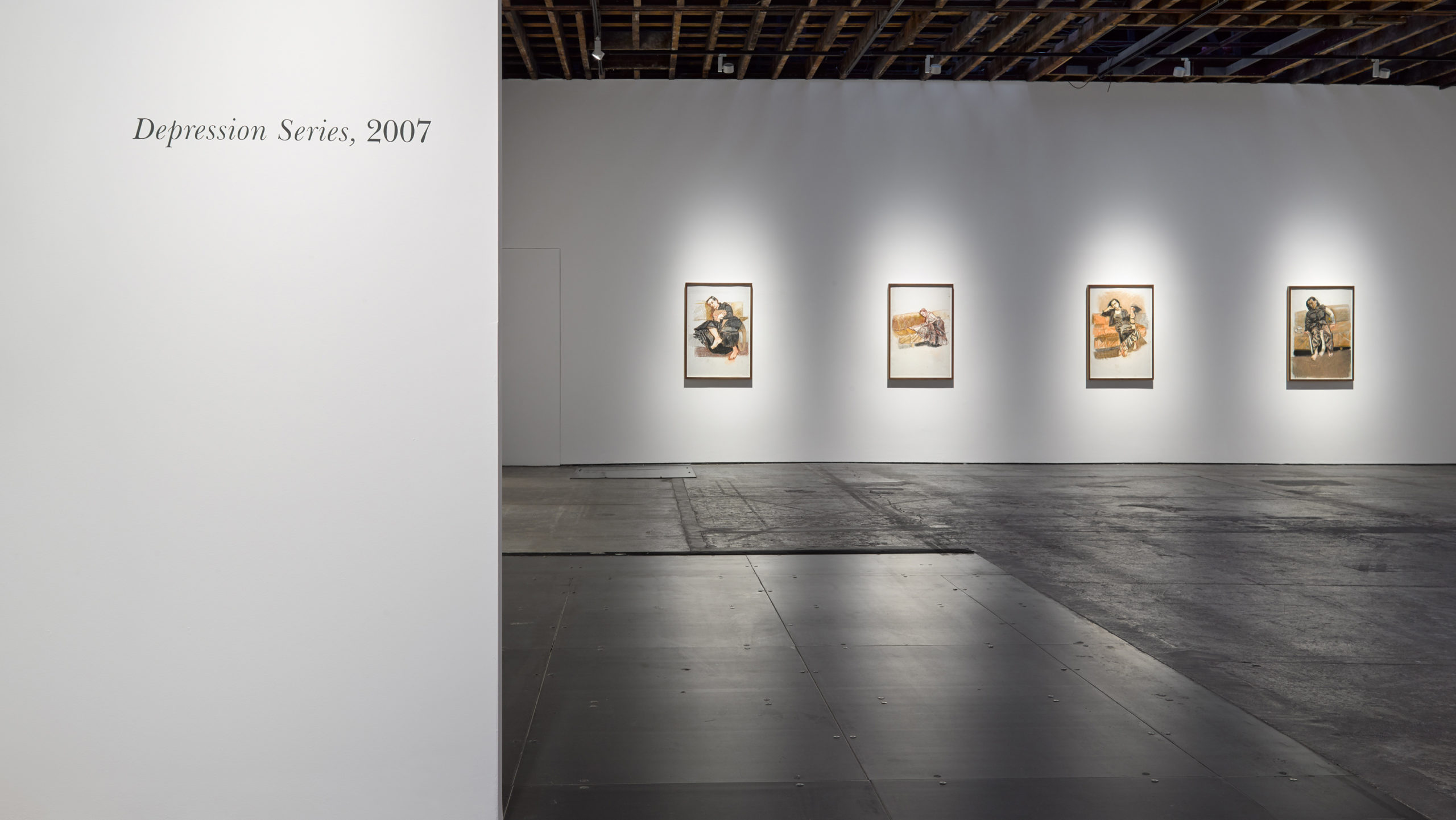

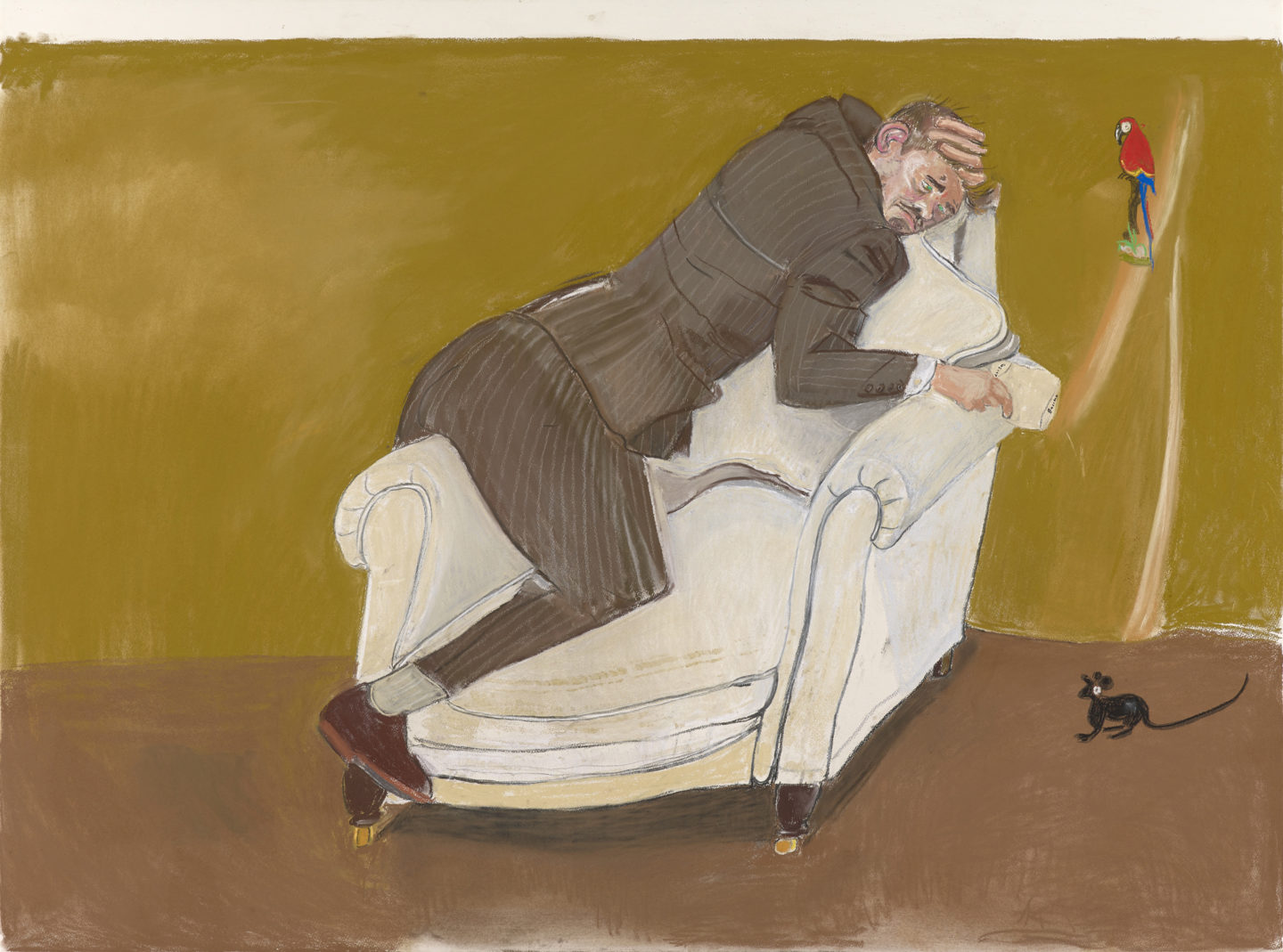

Depression Series

‘She hid these pictures for ten years because she was ashamed. She was ashamed of suffering from depression.’ — Nick Willing

The Depression series, 2007, is a suite of large-scale pastels born out of an especially debilitating depressive episode and Rego’s attempts to draw her way out of it. In reference to the series, Nick Willing says, ‘She hid these pictures for ten years because she was ashamed. She was ashamed of suffering from depression.’ Rego discusses the works publicly for the first time in Willing’s 2017 film Paula Rego: Secrets & Stories. The film aired in cinemas in Portugal for many weeks and the works were subsequently shown at House of Stories, the museum in Cascais dedicated exclusively to Rego’s work. Discussing the effect of the film and exhibition in Portugal, Willing says, ‘What happened was that every TV panel show and morning show would talk about depression. The Portuguese never talked about depression, it was a big taboo, but one of the things that Paula did, which is what she’s always done, is she broke the ice and allowed them to talk about it. She forced people to confront it and talk about it and open up.’

In the accompanying publication, Deborah Levy writes, ‘To encounter the 2007 series titled Depression, is to understand that the full spectrum of female emotional life has been embodied for us by a uniquely fearless artist.’

Grief

Pastel on paper on aluminium

119.2 x 160.2 cm

46 7/8 x 63 1/8 in

Paula Rego, Grief, 2015

More infoPublished in 1878, Eça de Queiroz’ novel Cousin Bazilio is a story of marriage, betrayal, blackmail and, ultimately, death that, set in bourgeois Portuguese society with a finely drawn cast and luxurious detail, intersects with many of the themes and motifs of Rego’s art. Grief, 2015, is one of a number of works inspired by scenes from the novel that make numerous connections between physical interiors and psychological states.

Sophia’s Friends

Pastel on paper on aluminium

110 x 130.2 cm

43 1/4 x 51 1/4 in

Paula Rego, Sophia’s Friends, 2017

More info‘The pretty pastel colours contrast with the fierce, secret, interior lives of these three girls, while the power relations between them are inflamed with Rego’s droll humour.’ — Deborah Levy

Writing about this work, Deborah Levy comments, ‘She is particularly astute on the legend of girlhood and its erotic charge. If some of us are nasty and some of are nice, mostly we are a mix of both, as in Sophia’s Friends, 2017. The pretty pastel colours contrast with the fierce, secret, interior lives of these three girls, while the power relations between them are inflamed with Rego’s droll humour.’

Rape

Pastel, conté and charcoal on paper

125.1 x 85.4 cm

49 1/4 x 33 5/8 in

Paula Rego, Rape, 2009

More infoThroughout her career, Rego has produced works that give visibility and a voice to sexual assault against women, addressing subjects specifically from the perspective of women’s experience as well as feminine power, physicality and strength. In 2008–2009, the artist created a multimedia work for the Foundling Museum that, based on an altarpiece, explores the violence effected on women’s bodies. One of the panels shows a rape, and this is an associated work. Writing about the Foundling Museum work in the Thames & Hudson book Paula Rego: The Art of Story, Deryn Rees-Jones notes that, ‘While the subject matter is stark, the dynamics of gesture and expression are not uncomplicated. What makes these images so moving is an approach that refuses sensationalism. These events in their horror must be recorded, Rego seems to insist, but they must also be represented in a manner that neither re-enacts trauma nor disempowers women.’

Misericordia

Pen, ink and watercolour on paper

41.9 x 59.4 cm

16 1/2 x 23 3/8 in

Paula Rego, Misericordia I (Pedro Galdos), 2001

More info

Pen, ink and watercolour on paper

41.9 x 59.4 cm

16 1/2 x 23 3/8 in

Paula Rego, Misericordia II, 2001

More info

Pen, ink and watercolour on paper

41.9 x 59.4 cm

16 1/2 x 23 3/8 in

Paula Rego, Misericordia III, 2001

More info‘Her gaze on the female body in all phases of life is brutally true and endearingly tender…’ — Deborah Levy

Completed in 2001, Misericordia is inspired by a nineteenth-century novella by the Spanish author Benito Pérez Galdós and, like other works on view, explores the mother-daughter relationship, in this instance against the backdrop of the artist’s own mother’s ailing health and eventual death. Writing in the accompanying publication, Deborah Levy comments, ‘There is rarely one fixed meaning in any image. Rego’s artfulness is to suggest a moment of change or contemplation, or to offer simultaneous narratives to fracture time. This can be seen in the multiple story lines of the Misericordia series… Her gaze on the female body in all phases of life is brutally true and endearingly tender, in this case, the bare-bottomed old women being helped to the bathroom or to get dressed, with the detail of a smart handbag (perhaps a whole abandoned life inside it) resting tragically on a cupboard.’

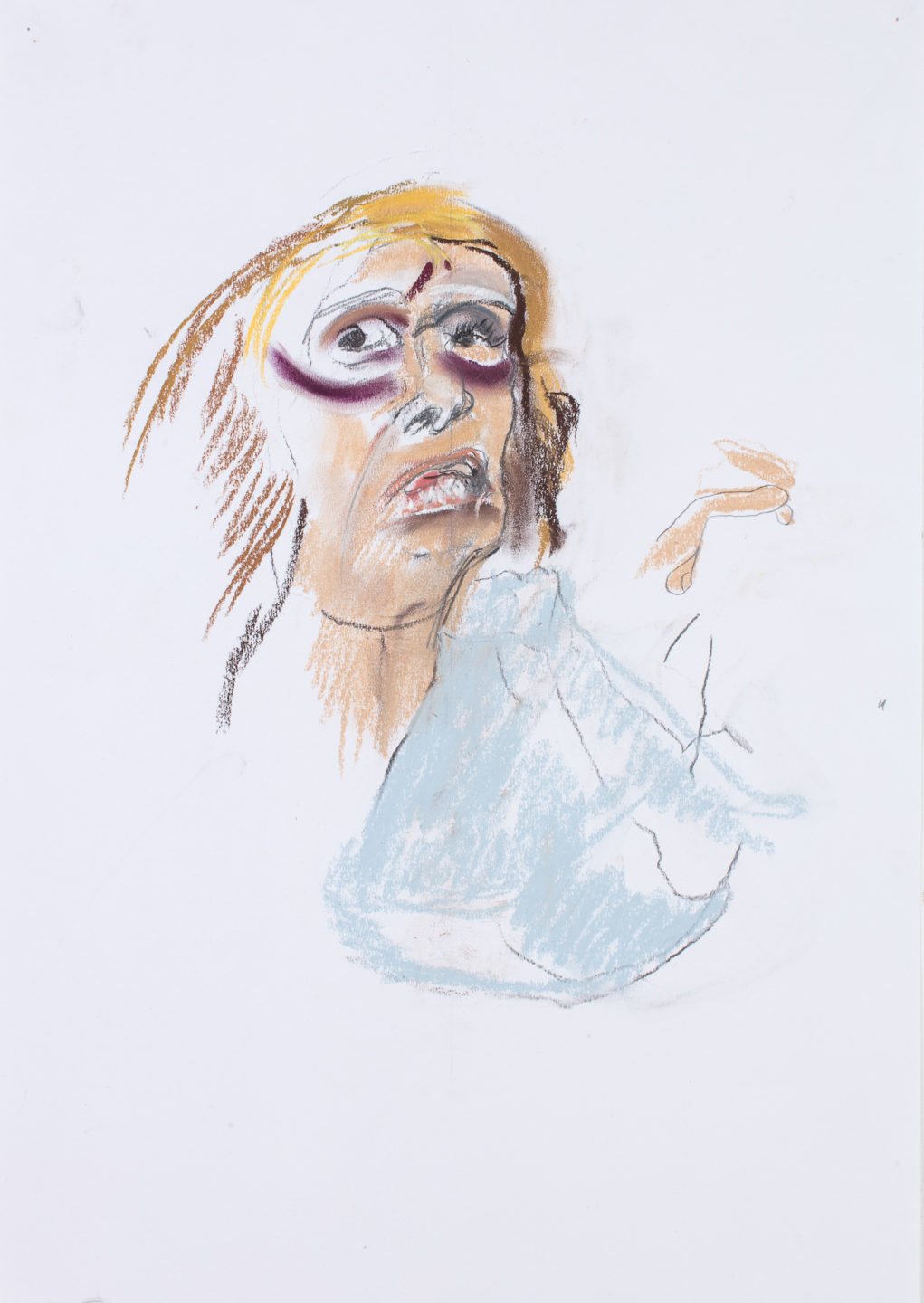

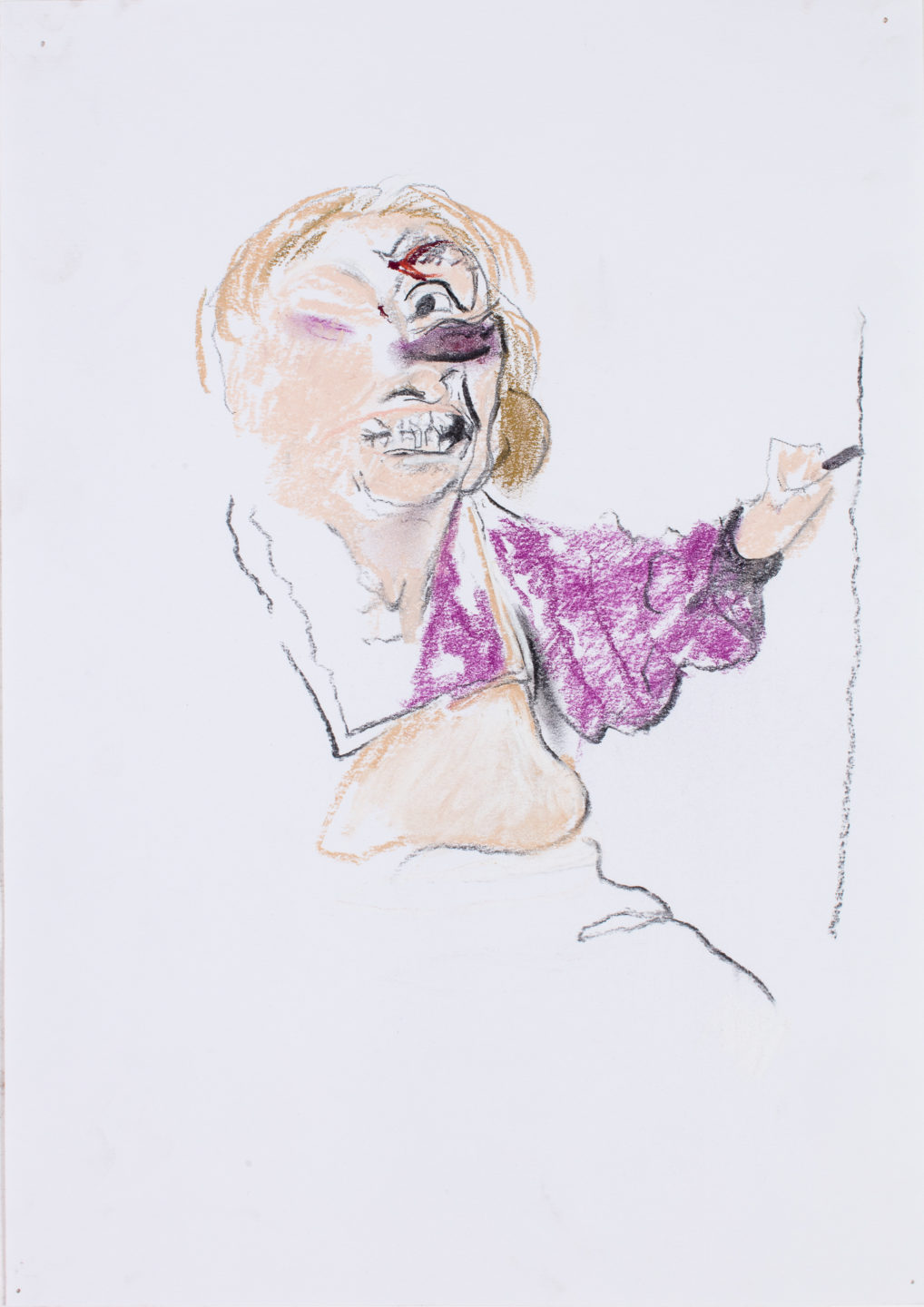

Self Portraits

‘If she is stripped of the radiance of youth, she is nevertheless radiant with the force of her own taboo-breaking gaze.’ — Deborah Levy

These self-portraits were completed in 2017, soon after the artist fell and badly injured her face. While Rego’s presence in her work – as creator, narrator or putative subject – is always palpable, she has made self-portraits only a handful of times in her career. In these characteristically unflinching works, Rego deftly captures her own likeness, bruised and out of shape, not as a means of expressing pain but because its physical effects gave her a reason to draw herself. As she said at the time, ‘I didn’t like the fall… but the self-portraits I liked doing. I had something to show.’ The power of transformation – caused by age, accident or anguish – is one theme of an exhibition that reveals Rego’s creative inspiration and motivation, and the candour of her vision, sustained across narratives, through motifs and over decades.

In the accompanying publication, Deborah Levy writes, ‘We see an older woman, her mouth wide open to reveal a snarl of crooked lower teeth, a wedding ring (perhaps) on the finger of her left hand, a pastel stick held in her right hand. If she is stripped of the radiance of youth, she is nevertheless radiant with the force of her own taboo-breaking gaze.’

About the artist

Born in 1935 in Lisbon, Portugal, Dame Paula Rego RA lives and works in London. The largest and most comprehensive retrospective of Rego’s work to date commenced this year at Tate Britain (7 July–24 October 2021) and will travel to Kunstmuseum Den Haag, The Netherlands (27 November 2021–20 March 2022) followed by Museo Picasso Malagá, Spain.

Other recent major solo exhibitions include Museum De Reede, Antwerp, Belgium (30 July–25 October 2021), and Paula Rego: Obedience and Defiance, curated by Catherine Lampert, which travelled from MK Gallery, Milton Keynes to the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh in 2019–2020 and was on view at the Irish Museum of Modern Art, Dublin from September 2020–May 2021. Rego’s work is in the collections of major museums including the British Museum, London, UK; National Gallery, London, UK; National Portrait Gallery, London, UK; Tate, UK and the Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester, UK.