Intimacy

Victoria Miro, London, 8 June–30 July 2022

Art Basel, Booth E3, 16–19 June 2022 (previews from 13 June 2022)

Njideka Akunyili Crosby, Milton Avery, Hernan Bas, María Berrío, Kudzanai-Violet Hwami, Chantal Joffe, Isaac Julien, Doron Langberg, Alice Neel, Chris Ofili, Celia Paul, Paula Rego, Do Ho Suh, Francesca Woodman, Flora Yukhnovich.

This summer, for the first time, a group exhibition at the gallery in London and a presentation at Art Basel share a common theme. In these works, a number of which have been created especially for the occasion, artists convey aspects of intimacy in its many forms: maternal, erotic, platonic, domestic. Here, intimacy is revealed through subject matter and also through aspects of scale, colour and touch, a reminder that the intimate is as much a communion between artist and their work as it is a depiction of private spheres, or lovers, family and friends.

Njideka Akunyili Crosby

Acrylic, colour pencil, collage, and transfers on paper

157.2 x 152.5 cm

61 7/8 x 60 1/8 in

On view in Basel: Njideka Akunyili Crosby, Garden Party, 2019

More info

Acrylic, transfers, colour pencil, charcoal and commemorative fabric on paper

182.9 x 152.4 cm

72 1/8 x 60 in

On loan from a private collection

On view in London: Njideka Akunyili Crosby, Cassava Garden, 2015

More infoDrawing on art historical, political and personal references, Njideka Akunyili Crosby creates layered compositions that, precise in style, nonetheless conjure the complexity of contemporary experience. The domestic spaces she depicts feel intimate yet are often suspended between continents and through time. Vegetation in the form of houseplants, wallpaper, patterned fabric or views of foliage snatched through windows often serves to break down distinctions between interior and exterior space. Up close, we notice a second wave of imagery. Applied using an acetone transfer technique are photographic images derived from sources including Nigerian pop culture and politics. It is partly through this labour-intensive process that Akunyili Crosby addresses the idea of cultural overlap and the complex layering of influences – personal, cultural, historical and political – on people and places.

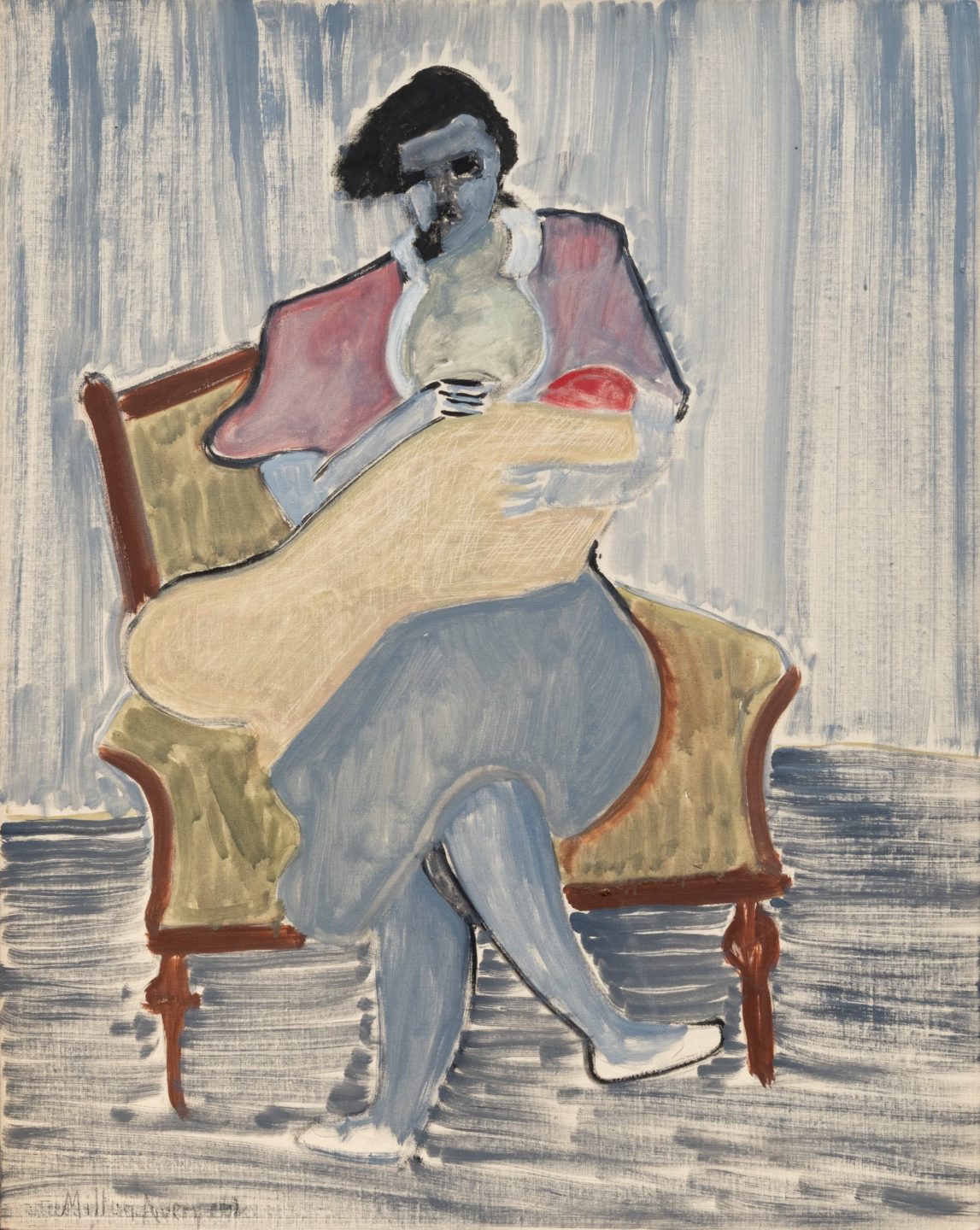

Milton Avery

Oil on canvas

122.2 x 81.2 cm

48 1/8 x 32 in

On view in Basel: Milton Avery, Female Artist, 1945

More info

Oil on board

61 x 91.4 cm

24 x 36 in

On view in Basel: Milton Avery, Artist Paints Artist, 1962

More info

Oil on board

76.2 x 61 cm

30 x 24 in

On view in London: Milton Avery, Nursing Mother, 1962

More info

Oil on canvas

127 x 106.7 cm

50 x 42 in

On view in London: Milton Avery, Green Stockings, 1964

More infoOne of the most influential artists of the twentieth century, Milton Avery (1885–1965) is celebrated for his luminous paintings of landscapes, figures and still lifes, which balance distillation of form with free, vigorous brushwork and lyrical colour. Avery pursued an independent and steadfast course throughout his career. Always drawing imagery from the world around him, in particular the landscapes and people he loved, his art is as intimate and accessible as it is towering in its ambition and achievement.

The archetypal theme of mother and child appears in paintings throughout Avery’s career, and Nursing Mother, 1962, is a crystalline reflection of his accumulated skills in portraying the figure. Green Stockings, 1964, is the last major painting he made of his wife, Sally Michel and, as with his late landscapes and seascapes, in this portrait he refines and condenses to achieve an image of intimacy and power. Female Artist, 1945, and Artist Paints Artist, 1962, feature Sally at work on a portrait of Avery himself, and are playful depictions of their creative partnership.

Hernan Bas

Acrylic on canvas

182.9 x 152.4 cm

72 x 60 in

On view in Basel: Hernan Bas, A conceptual artist #5 (A budding gilder, his dying houseplants get ‘The Midas Touch’), 2022

More info

Acrylic on linen

182.9 x 152.4 cm

72 1/8 x 60 in

On view in London: Hernan Bas, A conceptual artist #4 (Objectively neutral, each January he re-paints the walls of his studio an official ‘Color of the Year’), 2022

More infoHernan Bas is celebrated for works that, permeated by an aura of eroticism and decadence and loaded with codes and double-meanings, point to the intricacies of self-identity, while celebrating moments of transformation – the ordinary becoming extraordinary. These works follow a new theme, in which Bas’ protagonists engage in a variety of obsessive or eccentric pursuits that, deemed strange under ordinary circumstances, might be rationalised or even championed when considered as ‘conceptual art’. As ‘conceptualists’, the characters in the paintings are emboldened to indulge their passions – gilding the leaves of dying house plants, re-painting their studio annually with the ‘colour of the year’ – with vigour and seriousness as they construct their intimate, self-made worlds.

María Berrío

Collage with Japanese paper and watercolor paint on linen

96.5 x 61 cm

38 x 24 in

On view in Basel: María Berrío, The Interruption, 2022

More info‘The Interruption talks about intimacy interrupted. The viewer has disrupted a shared moment between two women, an unappreciated intrusion…’ — María Berrío

Based in Brooklyn, María Berrío grew up in Colombia. Her works, which are meticulously crafted from layers of Japanese paper, reflect on cross-cultural connections and global migration seen through the prism of her own history. Speaking about the works on view, the artist says: ‘The Interruption talks about intimacy interrupted. The viewer has disrupted a shared moment between two women, an unappreciated intrusion… We are observing an instance of shared sisterhood, those moments which only can be experienced and understood between women. It is in instances such as these that women learn the importance of having others to rely on and understand them, to share their specific joys and burdens. And it is here that they learn they must protect one another, to fight for their own rights to protect themselves, their bodies, and the choices they make with them. Sisterhood, here, is both shield and sword: without it, women cannot defend themselves nor forge alliances in the demand for empowerment and rights.

Kudzanai-Violet Hwami

Oil and acrylic on canvas

200 x 200 cm

78 3/4 x 78 3/4 in

On view in Basel: Kudzanai-Violet Hwami, Trauma pond 1, 2022

More info

Oil and acrylic on canvas

60 x 60 cm

23 5/8 x 23 5/8 in

On view in London: Kudzanai-Violet Hwami, Trauma pond 5, 2022

More info

Oil and acrylic on canvas

60 x 60 cm

23 5/8 x 23 5/8 in

On view in London: Kudzanai-Violet Hwami, Trauma pond 6, 2022

More infoBased in the UK, Kudzanai-Violet Hwami was born in Gutu, Zimbabwe and lived in South Africa from the ages of nine to seventeen. Her paintings combine visual fragments from a myriad of sources, such as online and archival images, and personal photographs, which collapse past and present. Autobiographic in nature, these are works that, ‘dealing with internal and private curiosities’, as the artist says, address how in a digitised world we use images to construct a sense of self, or experience and try to understand one another in a complex social reality.

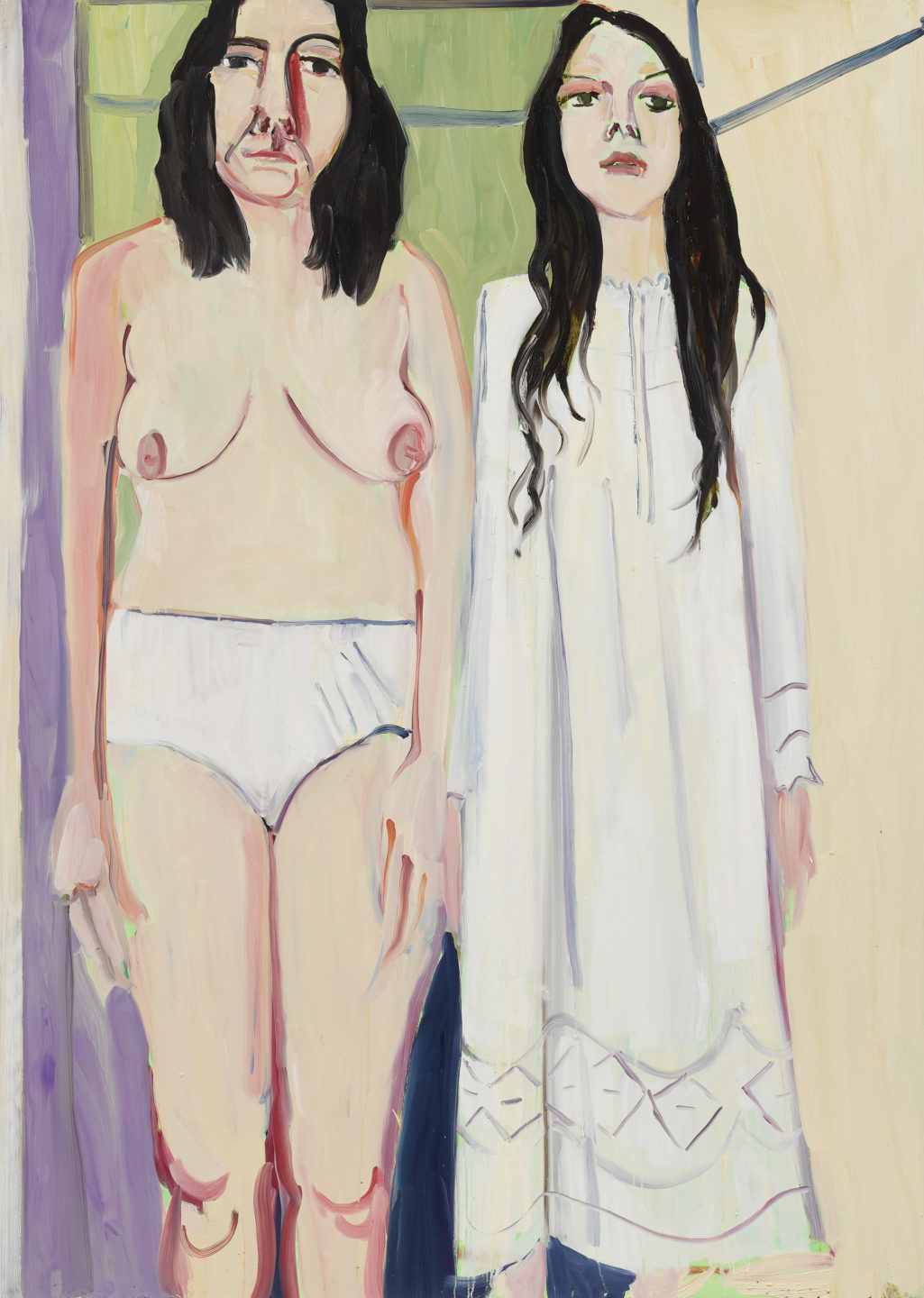

Chantal Joffe

‘Self-Portrait with Esme in a Nightie is part of a series of paintings I’ve been making since I was pregnant with my daughter Esme. I made this particular work in January 2022. We stand side by side and she’s almost 18 in the painting. It’s been a hard year for us but here we are side by side, still standing.’ — Chantal Joffe

Chantal Joffe brings a combination of insight and integrity, as well as psychological and emotional force, to the genre of figurative art. Defined by its clarity, honesty and empathetic warmth her work, whether intimate or monumental, is attuned to our awareness as both observers and observed beings, and is questioning, complex and emotionally rich.

Speaking about Self-Portrait with Esme in a Nightie, 2022, the artist says: ‘The work is part of a series of paintings I’ve been making since I was pregnant with my daughter Esme. I made this particular work in January 2022. We stand side by side and she’s almost 18 in the painting. It’s been a hard year for us but here we are side by side, still standing.’

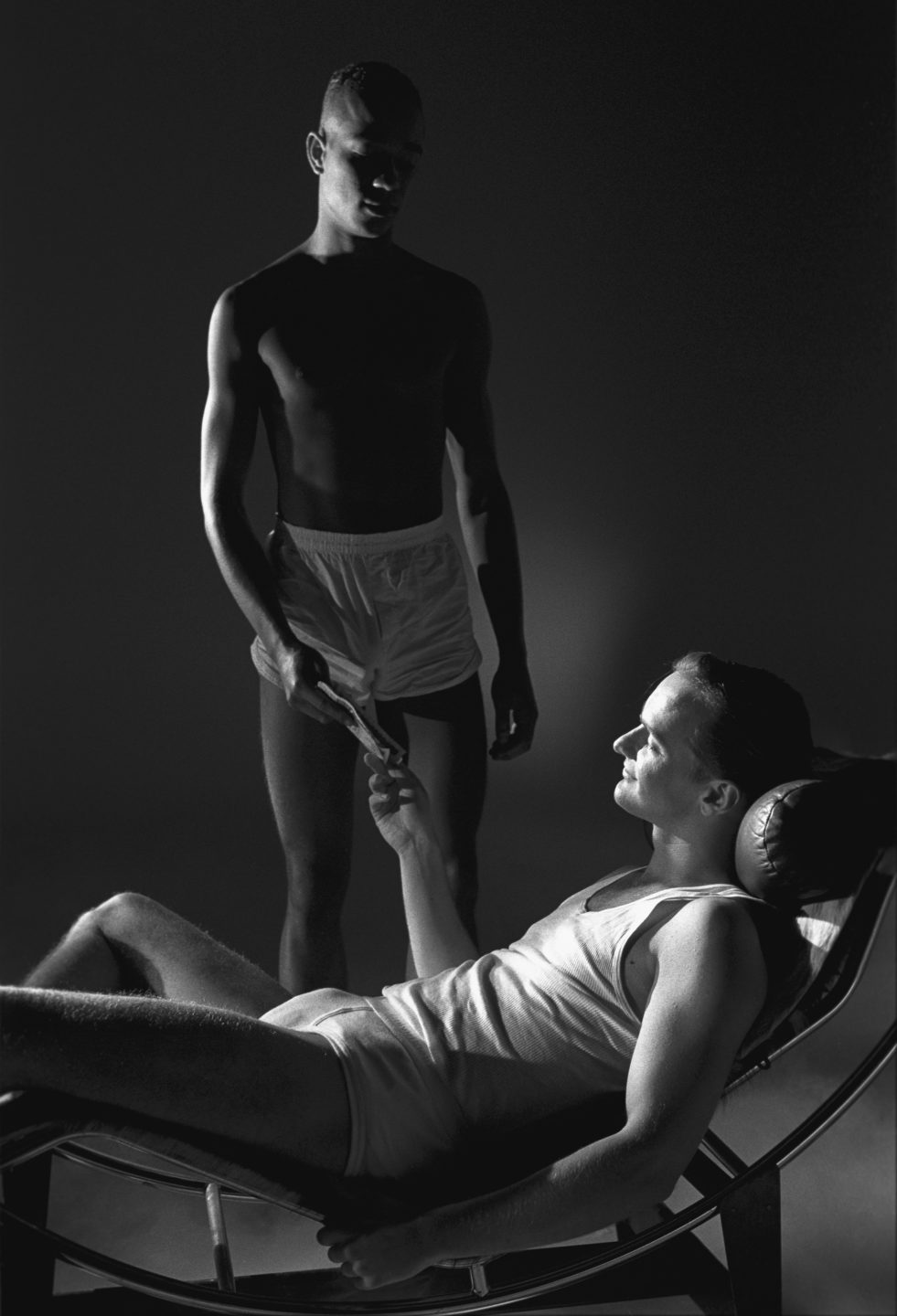

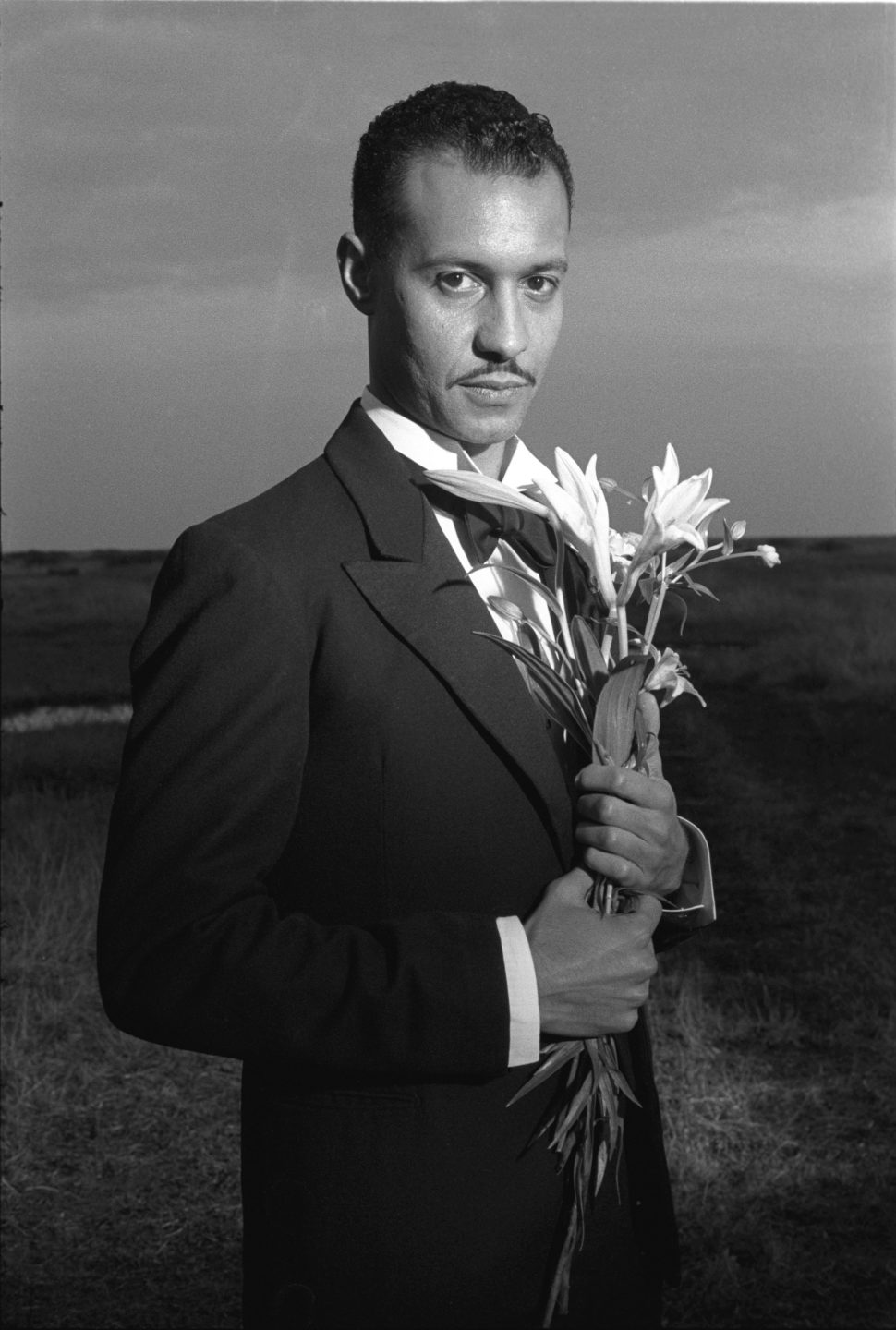

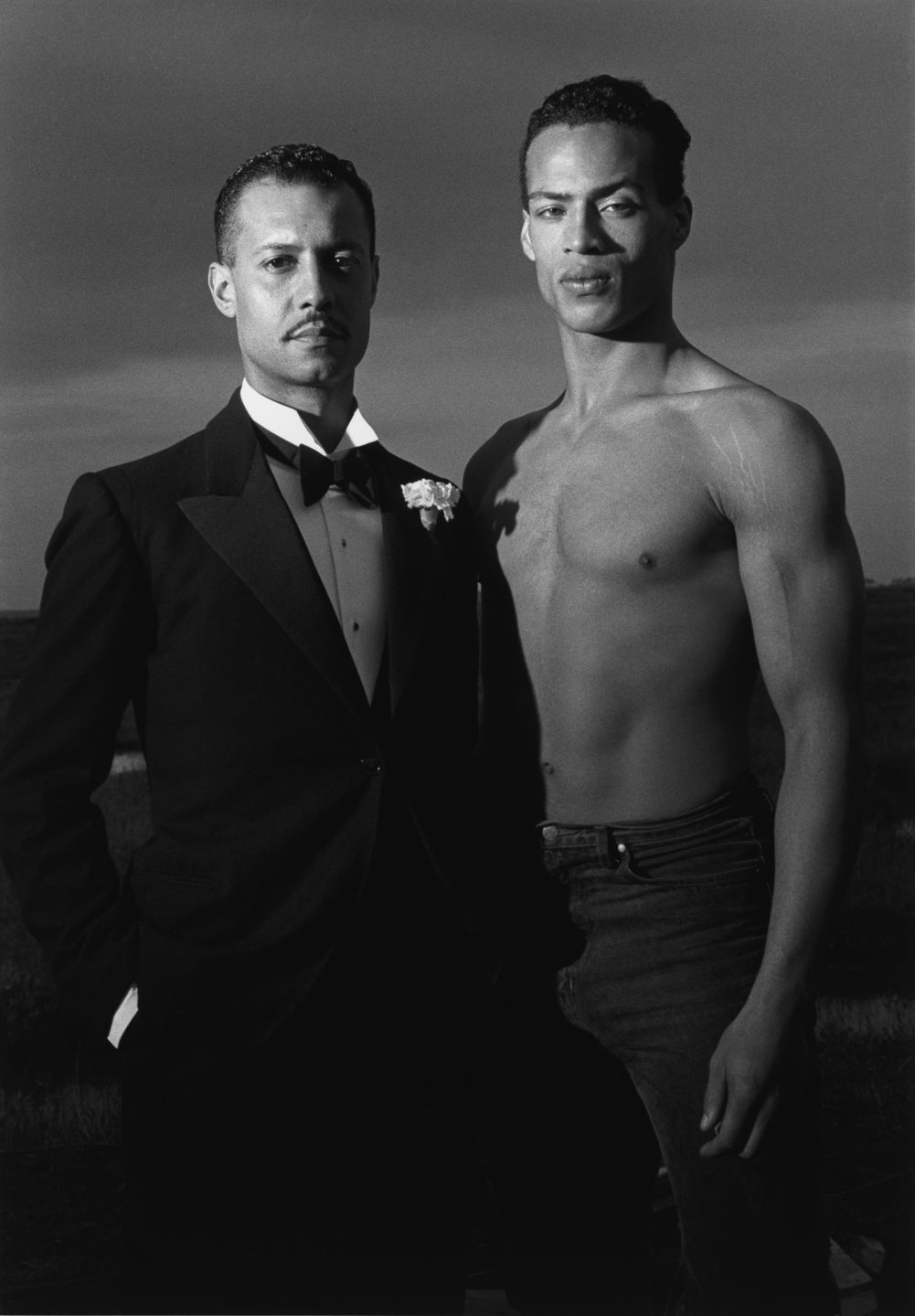

Isaac Julien

Kodak Premier print, Diasec mounted on aluminum

180 x 260 cm

70 7/8 x 102 3/8 in

On view in Basel: Isaac Julien, After George Platt Lynes (Looking for Langston Vintage Series), 1989/2017

More info

Ilford classic silver gelatin fine art paper, mounted on aluminum and framed

Framed size 74.5 x 58.1 cm

29 3/8 x 22 7/8 in

On view in London: Isaac Julien, Robert (Looking for Langston Vintage Series), 1989/2016

More info

Ilford classic silver gelatin fine art paper, mounted on aluminum and framed

Framed size 74.5 x 58.1 cm

29 3/8 x 22 7/8 in

On view in London: Isaac Julien, Looking for Langston (Looking for Langston Vintage Series), 1989/2016

More info

Ilford classic silver gelatin fine art paper, mounted on aluminum and framed

Framed size 74.5 x 58.1 cm

29 3/8 x 22 7/8 in

On view in London: Isaac Julien, Portrait (Looking for Langston Vintage Series), 1989/2016

More info‘The cradling of heads folded between the arms and limbs elevates these bodies to the Platonic state of eros, in the dynamic between intimacy and desire.’ — Isaac Julien

Isaac Julien’s seminal work Looking for Langston, 1989, is a lyrical exploration – and recreation – of the private world of poet, social activist, novelist, playwright, and columnist Langston Hughes (1902–1967) and his fellow black artists and writers who formed the Harlem Renaissance during the 1920s. The 1989 film is a landmark in the exploration of artistic expression, the nature of desire and the reciprocity of the gaze, and would become the hallmark of what B. Ruby Rich named New Queer Cinema. Aspects of the film and its multi-layered narratives of memory and desire, expression and repression, are revisited and expanded upon in these photographic works.

Speaking about After George Platt Lynes, the artist says: ‘Choreographing intimacy is intricate; it can be witnessed in the way in which bodies are sculptured in the space between the light and dark. This foregrounded chiaroscuro effect is mirrored above their heads, in the whispers of light and dark undulating the harp shape above them. The cradling of heads folded between the arms and limbs elevates these bodies to the Platonic state of eros, in the dynamic between intimacy and desire.’

Doron Langberg

‘Intimacy and closeness are at the centre of my practice. Whether it’s a portrait of a friend or depictions of a couple in bed, I want to express the multivalent and complex nature of relationships, highlighting our connectedness to one another.’ — Doron Langberg

Doron Langberg’s paintings, luminous in colour and often large in scale, celebrate the physicality of touch – in subject matter and process. Depicting himself, his family, friends and lovers, the broad scope of subjects and experiences in his work is connected by Langberg’s deeply felt use of paint. His intimate yet expansive take on relationships, sexuality, nature, family and the self proposes how painting can both portray and create queer subjectivity.

Alice Neel

Oil on canvas

50.8 x 40.6 cm

20 x 16 in

On view in London: Alice Neel, Mother and Child, 1938

More infoAlice Neel (1900–1984) is widely regarded as one of the foremost American artists of the twentieth century. Neel developed a signature approach, creating daringly honest paintings of her family, friends, neighbours, art world colleagues, writers, poets, artists, actors, activists, and more. Her works, which are forthright and intimate, engage overtly and quietly with political and social issues. Always working from life and memory, Neel’s ability to depict those around her with unfazed accuracy, honesty, and compassion displays itself throughout her work.

Throughout her life, Neel was interested in conveying the complexities and nuances of familial relationships. While candour and empathy are hallmarks of Neel’s art, her paintings of women and children, such as Mother and Child, 1938, are especially expressive of intimacy and compassion, as seen through the prism of her own experience as a woman and a mother.

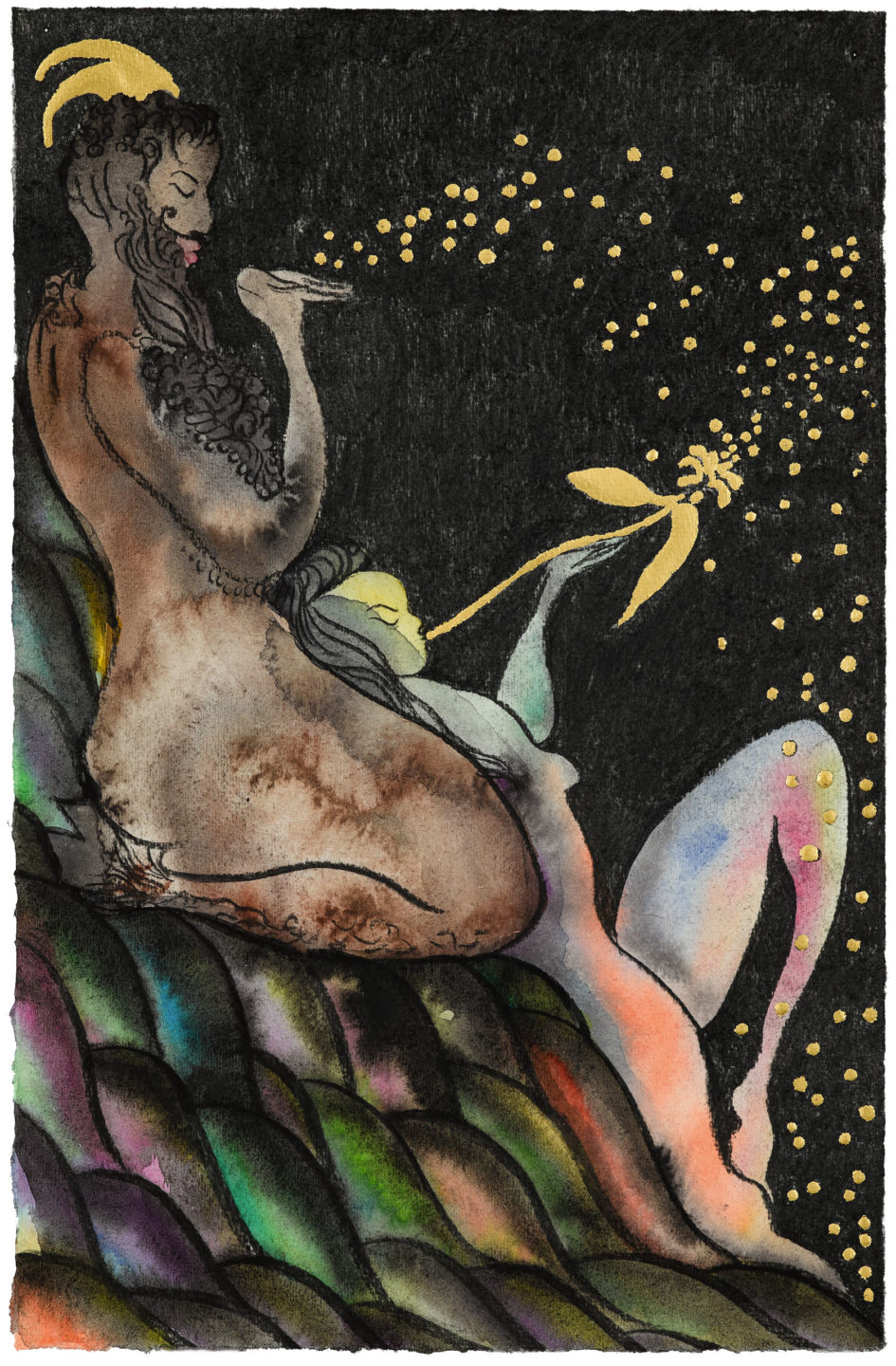

Chris Ofili

Oil on linen

310 x 200 x 4 cm

122 1/8 x 78 3/4 x 1 5/8 in

On view in Basel: Chris Ofili, It’s All Over Your Body, 2015

More info

Watercolour, charcoal and gold leaf on paper

39.5 x 25.7 cm

15 1/2 x 10 1/8 in

On view in London: Chris Ofili, Satyr Night (waterfall), 2020

More info

Watercolour, pastel, gold leaf and charcoal on paper

38.9 x 25.9 cm

15 1/4 x 10 1/4 in

On view in London: Chris Ofili, Dancers in Pink 3, 2020

More infoChris Ofili’s It’s All Over Your Body, 2015, encapsulates a kind of alchemy, a generation of energy. The painting is indicative of the artist’s continued interest in the kinds of narrative found in classical mythology, and while this image does not represent a specific story, a sense of an other-worldly or super-human force coming into being is evident. We view a male and female figure locked in an embrace within an embryonic egg-like form, symbolic of both creation and containment. Surrounding this radiant, flame-engulfed space is a darker ring inhabited by leopards and panthers which pace the perimeter. Beyond, a pattern of dots attempts to form an image, appearing almost as a cosmic constellation, while elsewhere a spray of iridescent dots falls over the figures.

The work also explores the fine line that exists between decoration and camouflage: the black panther is in fact a leopard which, too, has a pattern of all-over spots; however, these are masked by an excess of dark pigment in the pelt. Ofili’s composition opens up multiple perspectives: the scene can at once be read from overhead, as though the figures are located in an ovoid area at some depth from the animals circling above, or as a vertical slice through space. The text in the bottom left corner of the painting forms another base layer: a ground of gold and black, the text slipping off the canvas as the image slides down its surface. It’s All Over Your Body is exemplary of Ofili’s incorporation of the symbolic, the imagined and the real in his paintings, unified as a singular, vibrant and sensuous visual narrative.

In Satyr Night (waterfall), 2020, one of a number of recent paintings and works on paper that draws upon the myth of the satyr, Ofili repositions his subject away from conventional depictions of wild, Dionysian conduct with a sensitive representation in which his mythical figures appear lovingly at rest. Here, the nocturnal air is punctuated by the lush, kaleidoscopic colours of a waterfall, while gold leaf denotes the satyr’s horns, a flower held by a nymph, and dots that read as a shower of droplets exchanged by the couple. Gold leaf denotes the flowers held in the mouths of Ofili’s Dancers in Pink 3, 2020, who appear in shadow, framed by pink, as if caught up in their own realm, a space of rapturous abandon.

Celia Paul

‘When I enter a public gallery where there are great paintings of various sizes and styles, my eye is invariably drawn to the image which conveys an intense compassionate focus, often on a small scale. I would like to produce work with a similar concentrated power.’ — Celia Paul

Celia Paul is renowned for her intimate depictions of people and places she knows well, among them her home and studio opposite the British Museum, the subject of Room, Great Russell Street, Morning, 2020. In this highly atmospheric work, the simple architecture of the interior becomes transfigured by the play of light, a physical space becoming powerfully psychological. Self-portraiture is a cornerstone of Paul’s art and in works such as In the Studio, Night, 2021, she opens up a painterly and conceptual dialogue between the dual role of subject and artist – caught between self-possession and self-scrutiny – as well as offering an extended consideration on the passage of time and of the essential dualities of the medium – its ability to capture qualities of form, light and atmosphere, and its material presence.

In response to the theme of Intimacy, the artist writes, ‘When I enter a public gallery where there are great paintings of various sizes and styles, my eye is invariably drawn to the image which conveys an intense compassionate focus, often on a small scale. I am thinking of Vermeer, of Van Gogh. I am thinking of Gwen John: her intimate work holds its own in the company of paintings on the grandest scale. I would like to produce work with a similar concentrated power.’

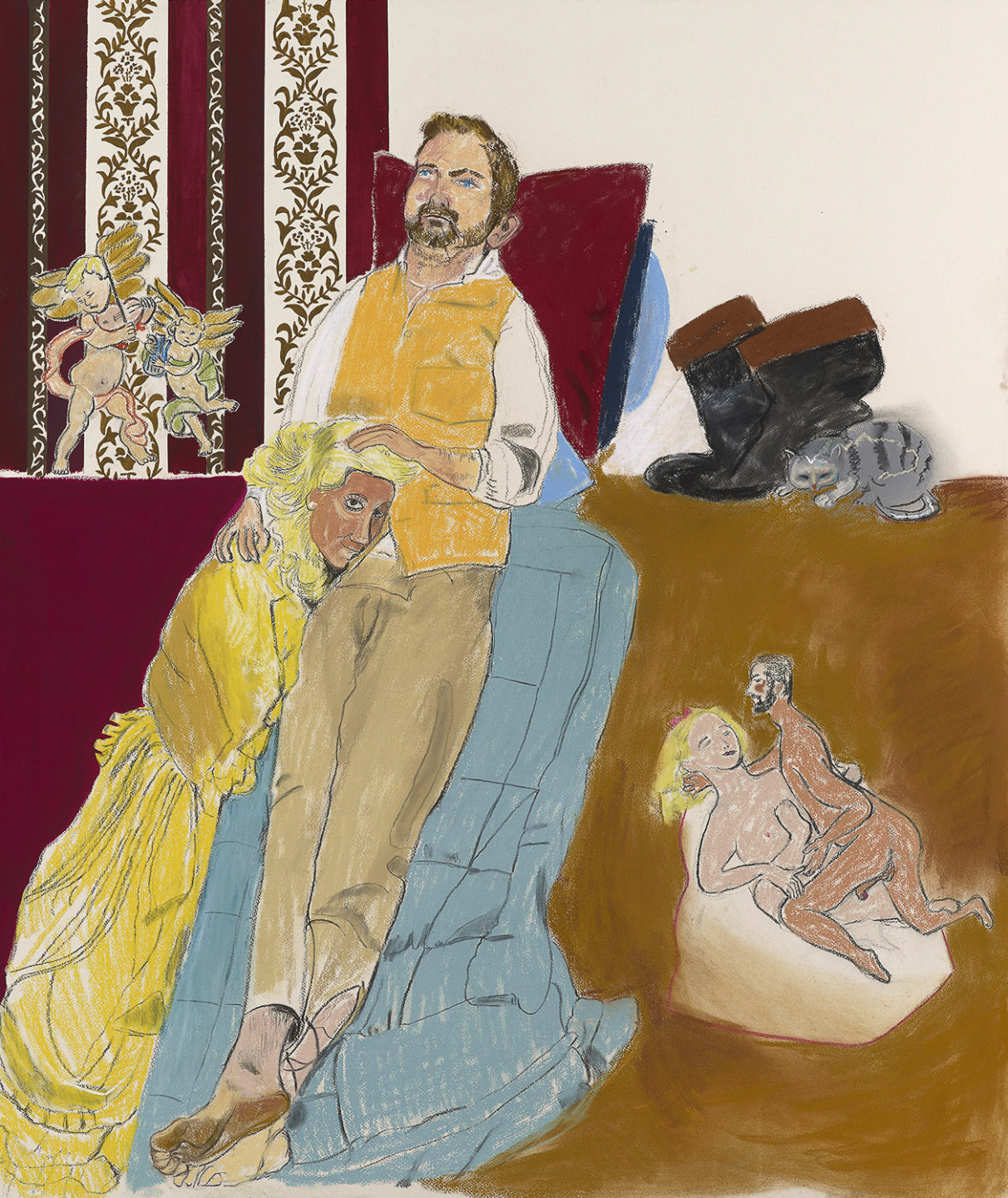

Paula Rego

An artist of uncompromising vision and a peerless storyteller, Paula Rego (1935–2022) brought immense psychological insight and imaginative power to the genre of figurative art. Drawing upon details of her own extraordinary life, on politics and art history, on literature, folk legends, myths and fairytales, Rego’s work at its heart is an exploration of human relationships, her piercing eye trained on the established order and the codes, structures and dynamics of power that embolden or repress the characters she depicts.

Published in 1878, Eça de Queiroz’ novel Cousin Bazilio is a story of marriage, betrayal, blackmail and, ultimately, death that, set in bourgeois Portuguese society with a finely drawn cast and luxurious detail, intersects with many of the themes and motifs of Rego’s art. On view are two works inspired by scenes from the novel. The Paradise of the title refers to the interior in which two characters from the novel, Luisa and Bazilio, conduct an affair.

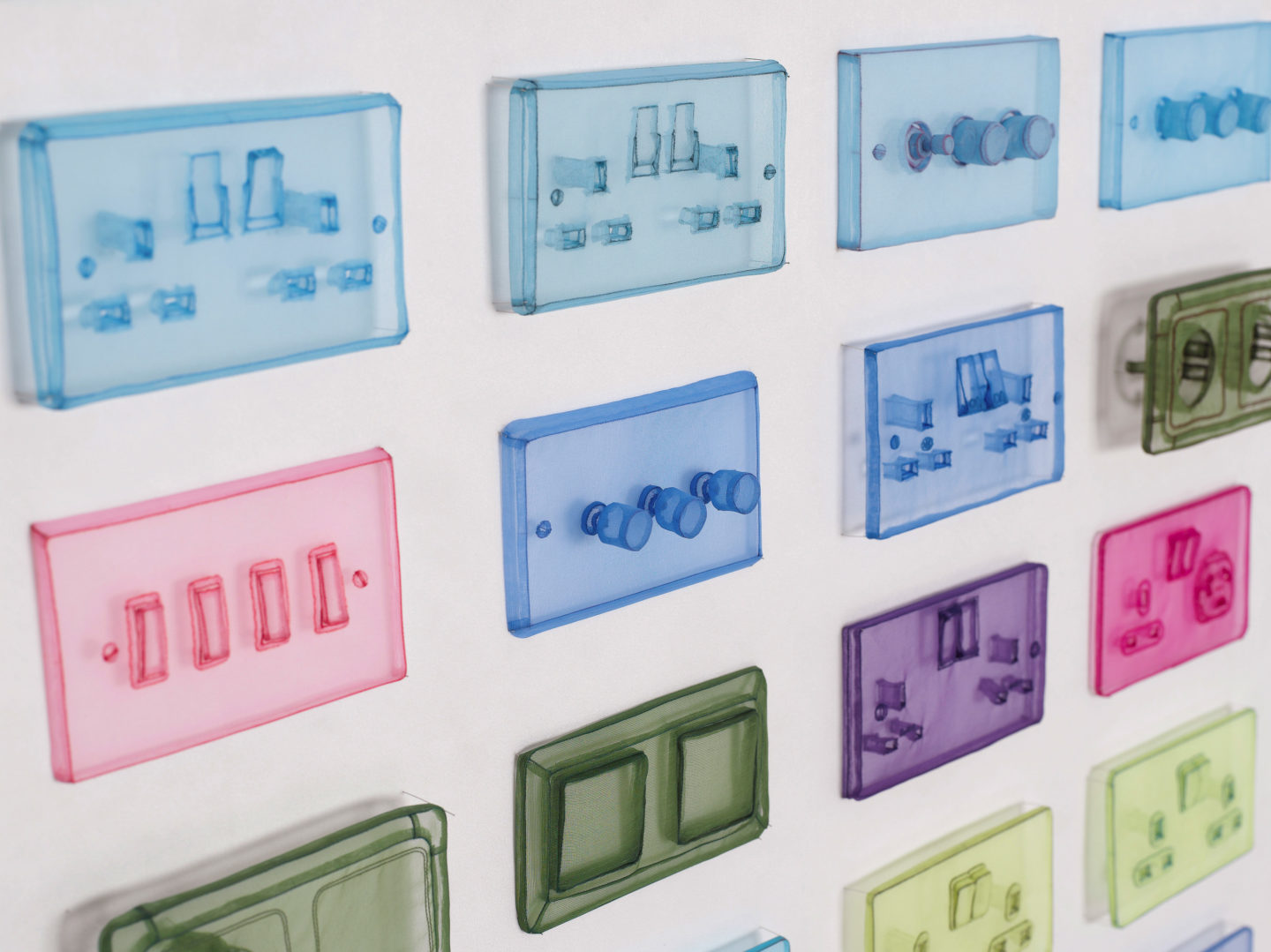

Do Ho Suh

Polyester fabric and stainless steel wire

154.8 x 218.8 cm

61 x 86 1/8 in

On view in Basel: Do Ho Suh, Sockets/Switches (Rectangular/Horizontal): Berlin, Horsham, London, New York, Seoul, Venice,, 2021

More info

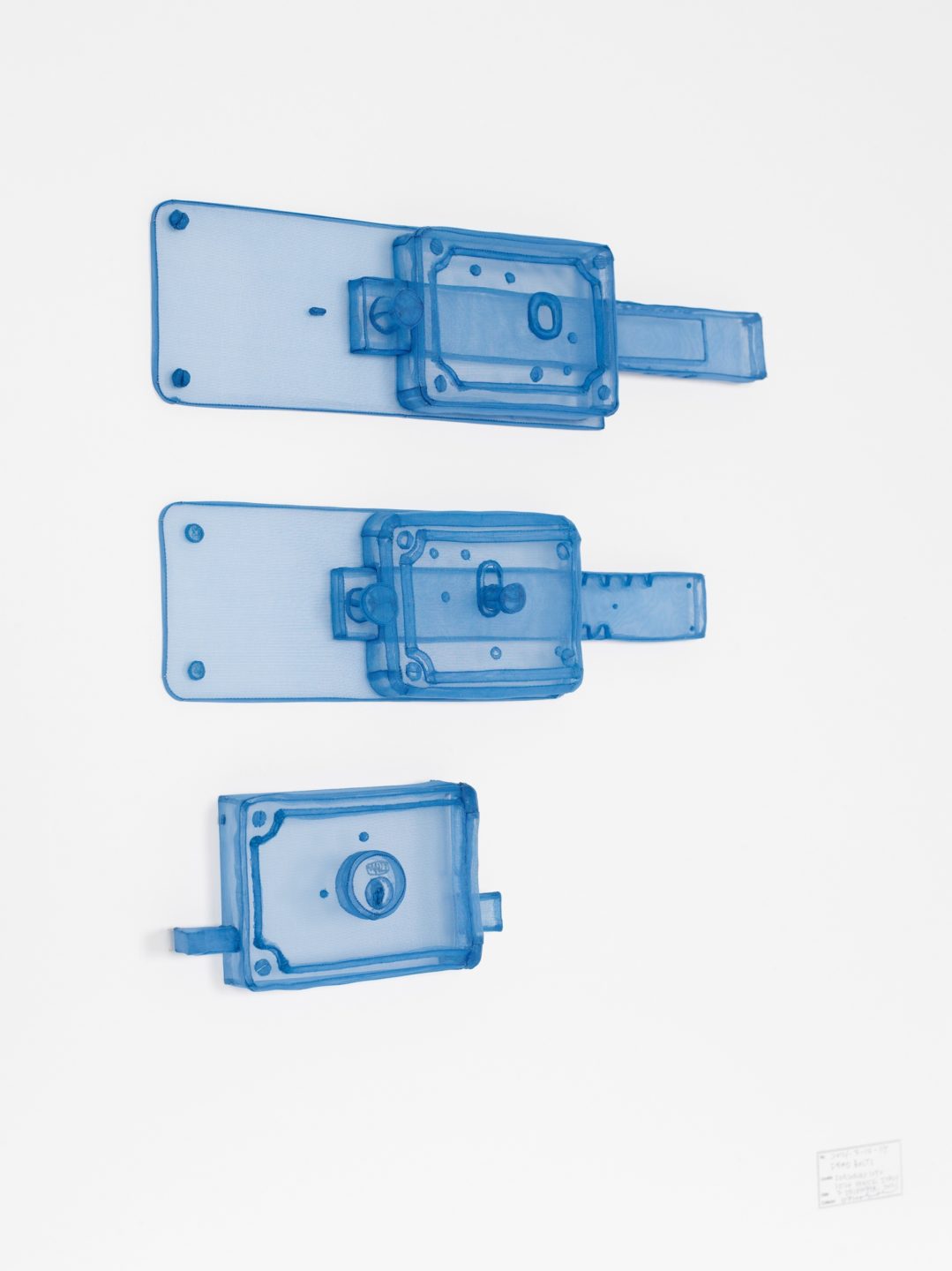

Polyester fabric and stainless steel wire

75 x 77 cm

29 1/2 x 30 1/4 in

On view in Basel: Do Ho Suh, Deadbolts: Dorsoduro 1050 – 30124 Venice, Italy, 2021

More info

Polyester fabric and stainless steel wire

121.1 x 86 cm

47 5/8 x 33 7/8 in

On view in Basel: Do Ho Suh, Entrance, Dorsoduro 51, Fondamenta Zattere Ai Saloni, 30124 Venice, Italy, 2021

More info‘I relate architecture to clothing and the Specimen are like pressure points or the anatomical parts of a building – there is actually something very bodily and intimate about them for me.’ — Do Ho Suh

Do Ho Suh has long ruminated on the idea of home as both a physical structure and a lived experience. In work for which he is widely celebrated, the artist meticulously constructs proportionally exact replicas of dwelling places, architectural features, or household fixtures and appliances from stitched planes of translucent, coloured polyester fabric. Drawn from places the artist has inhabited, such as his childhood home or Western studios and apartments, these delicately precise, weightless impressions give form to ideas about migration, transience and shifting identities.

Speaking about the works on view, the artist says: ‘Much of my work is about the body and how we clothe ourselves to move through the world. During lockdown, I had a strong urge to return to my Specimen series. I relate architecture to clothing and the Specimen are like pressure points or the anatomical parts of a building – there is actually something very bodily and intimate about them for me. Our relationship with quotidian objects within the home – the handles, switches and sockets that punctuate the anatomy of our buildings and that we touch all the time – has become fraught during the pandemic, but we’ve also become intensely familiarised with those forms and spaces. Each object is one that I have a relationship with, that I have touched on a regular basis at some point in my life. The process of measuring the spaces for the patterns is also a loving, caressing gesture for me, it’s how I make sense of my surroundings.’

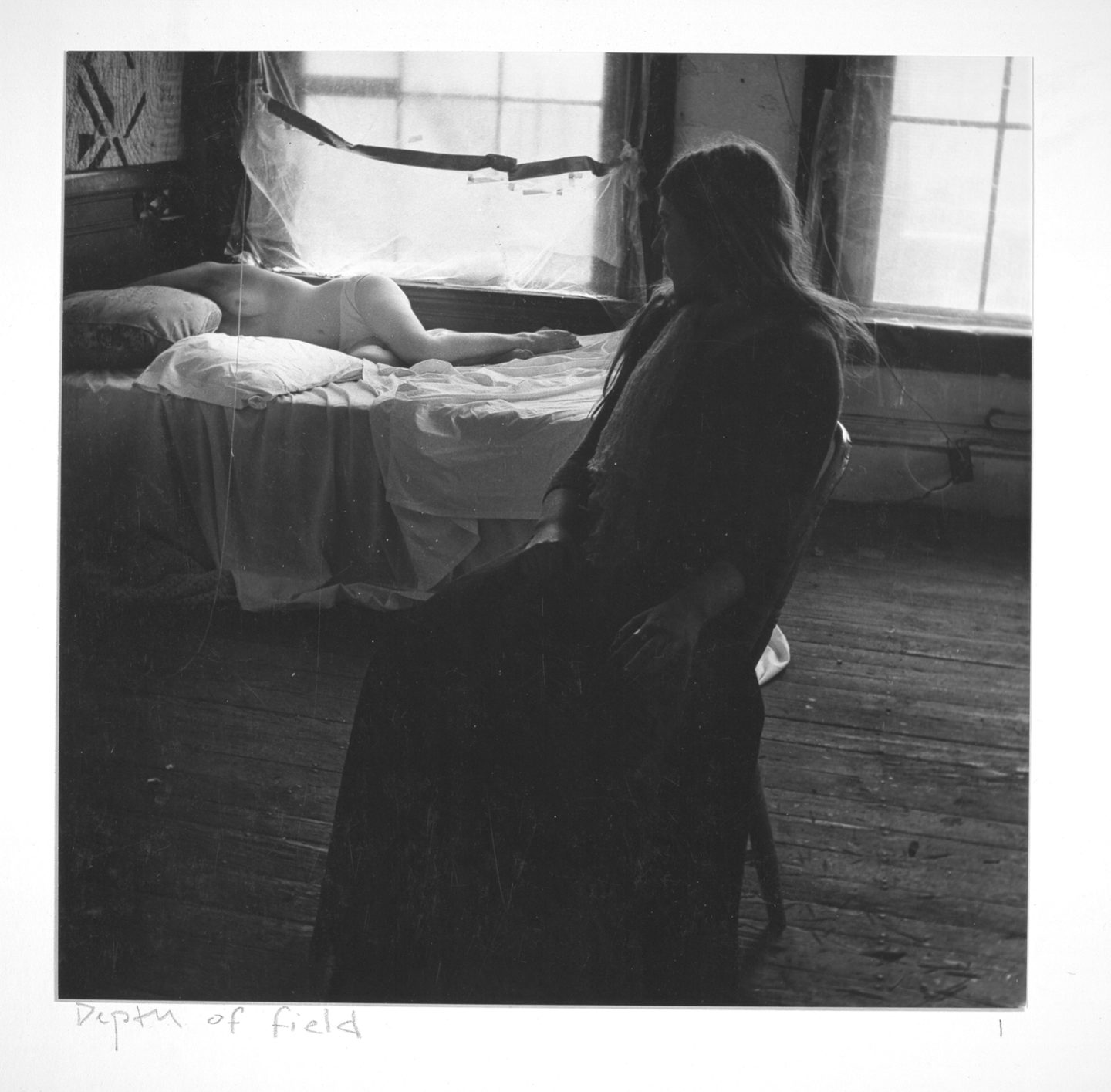

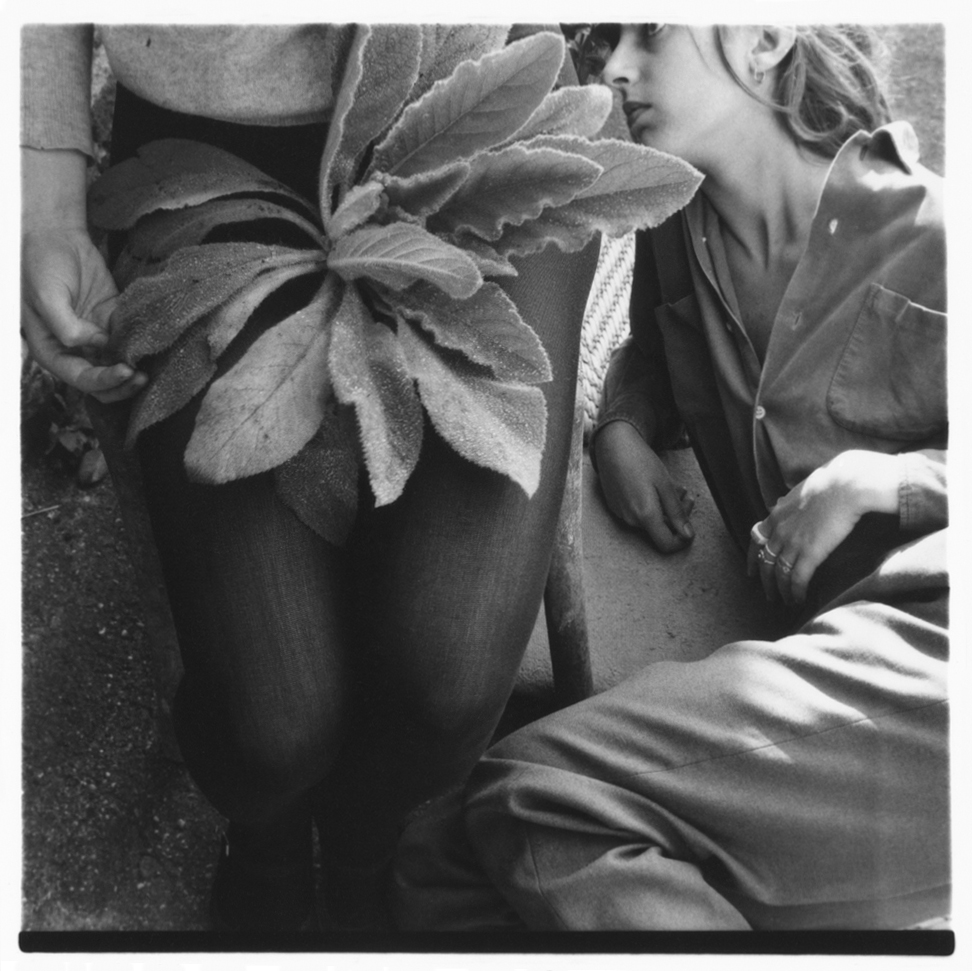

Francesca Woodman

Francesca Woodman (1958–1981) produced an extraordinary body of work acclaimed for its singularity of style and range of innovative techniques. From the beginning, her focus was on the relationship with her body as both the object of the gaze and the active subject behind the camera, and in the works on view we see a testing of the boundaries of bodily experience in addition to a sophisticated understanding of space and form, derived from Woodman’s knowledge of art history and her engagement with and enquiry into her medium.

Often photographed in empty or sparsely furnished rooms, in some images Woodman quite literally becomes one with her surroundings, with the contours of her form blurred by movement, or altered by light and shadow. In others she uses the physical body literally as a framework in which to construct and alter a material identity, summoning classical or religious imagery through formal or symbolic means.

Flora Yukhnovich

Oil on linen

70 x 60 cm

27 1/2 x 23 5/8 in

On view in London: Flora Yukhnovich, Beautiful Little Fool, 2022

More infoFlora Yukhnovich is acclaimed for paintings that, fluctuating between abstraction and figuration, transcend painterly traditions to fuse high art with popular culture and intellect with intuition. The artist has described her process as ‘searching for a language which sits between figuration and abstraction. I like the idea of combining these two art historical moments which have become highly gendered: the pretty Rococo imagery and the machismo of abstraction. But really abstraction and figuration don’t feel separate to me. They are two different points in the same process, part of a spectrum which ranges from very loose, abstracted marks through to tightly articulated figuration. I do want the resulting paintings to remain open and ambiguous despite their figuration. The viewer has to fill in the looser areas in their mind and I hope that leads to a multiplicity of different readings.’