Stephen Willats: Concepts and Construction Works, 1961–1965

24–27 March 2021

VIP preview from 24 March, 1pm GMT

Public days: 25 March, 1pm GMT—27 March, 11pm GMT

Victoria Miro is delighted to participate in Art Basel OVR: Pioneers with a focused selection of important works from the early 1960s by Stephen Willats.

For six decades, Stephen Willats (born in London in 1943) has concentrated on ideas that today are ever-present in contemporary art: communication, social engagement, active spectatorship and self-organisation, and has initiated many seminal multi-media art projects. He has situated his pioneering practice at the intersection between art and other disciplines such as cybernetics – the hybrid post-war science of communication – advertising, systems research, learning theory, communications theory and computer technology. In so doing, he has constructed and developed a collaborative, interactive and participatory practice grounded in the variables of social relationships, settings and physical realities. Rather than presenting visitors with icons of certainty he creates a random, complex environment which stimulates visitors to engage in their own creative process.

The conceptual underpinning of these early works lies in Willats’ interest in the broad tradition of constructivism to which he had first been exposed between 1958 and 1961 when working as a gallery assistant at the Drian Galleries, London. At the Drian, Willats was introduced to international avant-gardes and met and helped to organise exhibitions by artists including the constructivists Yaacov Agam and Gyula Kosice. Of particular influence was the exhibition Construction: England: 1959–60 held at the gallery in January 1961, which introduced Willats to English constructivists including Stephen Gilbert and Kenneth and Mary Martin, as well as other artists involved in education, social constructivism and socialism, and helped to ground his move away from the idea, and modernist ideal, of the art object towards a wider consideration of its social role. Invigilating at these important though often sparsely attended exhibitions, Willats began to read books on philosophy by Maurice Merleau-Ponty and Marshall McLuhan, among others, and to create his own notebooks in which he considered the role and meaning of art and how artists could connect.

In 1960, Willats also began working part time at the New Vision Centre (NVC) in Marble Arch, which showed experimental European work by, for example Piero Manzoni and the Zero group, as well as abstract painting by a broad range of international artists. In 1962, Willats started to attend the Groundcourse – a radical and influential experiment in art education at Ealing Art College which included exercises in which social processes were privileged over physical constructions, and flows of information took precedence over static models. In tandem, reading philosophy and theories including the idea of the random variable, derived from the mathematical model of uncertainty (which was to influence much of his kinetic work from the period), he established the core principle of his work; that the artwork is activated through the dynamic between itself and each viewer, or participant, and that this experience is different for every individual.

This half-decade period, in which Willats studied subjects including semiology, language codes and behaviourism, had studio visits with RD Laing and Edward de Bono, among many other notable figures, became a progressive educator himself and even took desk space in an advertising agency, today seems almost mythical in its optimistic embrace of the new and cross-pollination of ideas from the worlds of art, science and technology. There was intensive discussion around the role of the artist, what art could – should – be and its function in society. As Willats says, ‘People were in communication with each other that weren’t in communication before. There was a moment when everyone was excited about everybody else.’

Art Basel OVR: Pioneers is dedicated to artists who have broken new aesthetic, conceptual, or socio-political ground. Victoria Miro’s presentation of works by Stephen Willats is also available to view on Vortic, the leading virtual and augmented reality platform for the art world.

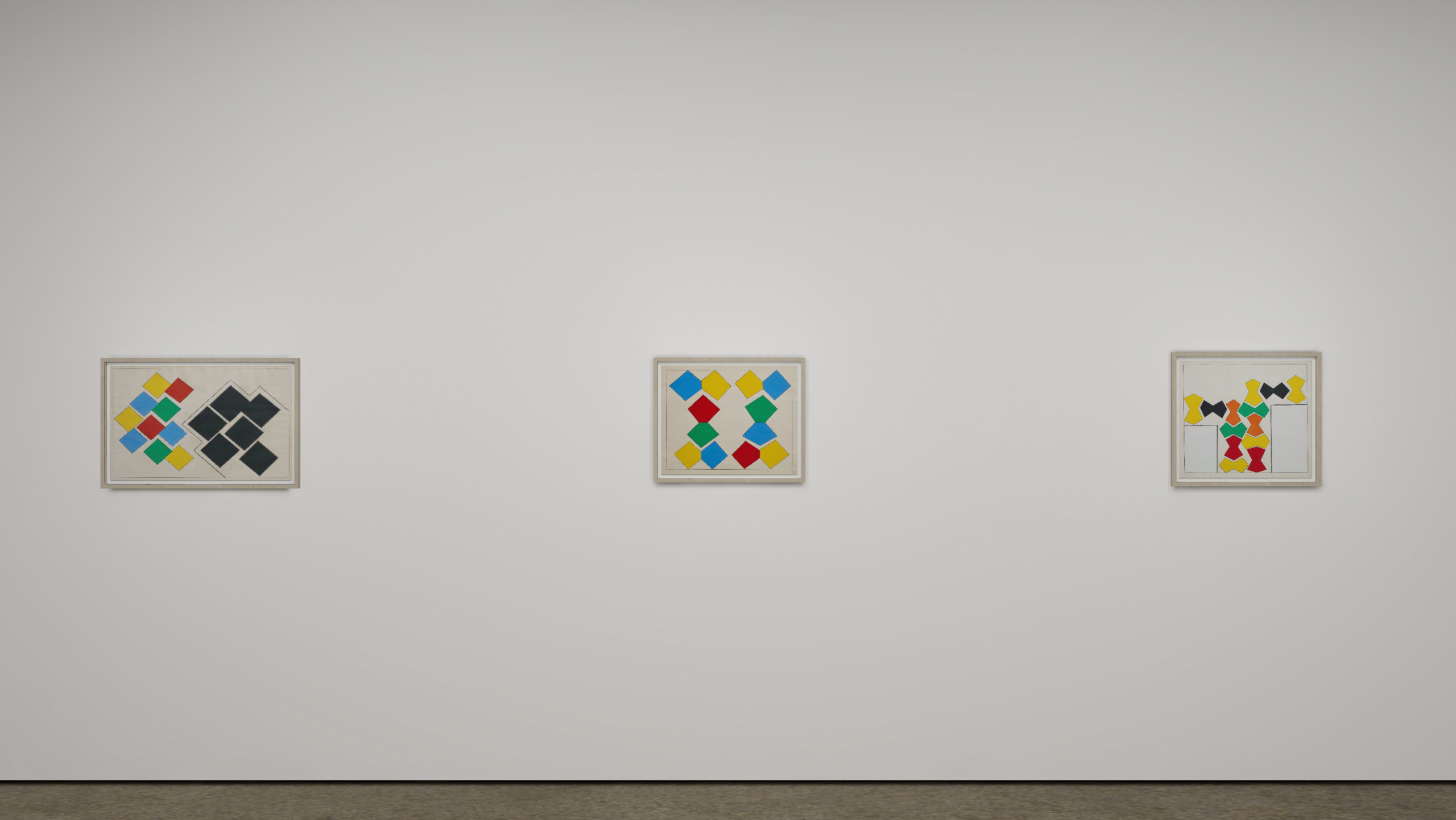

Paintings

Oil on canvas

50.5 x 40.5 cm

19 7/8 x 16 in

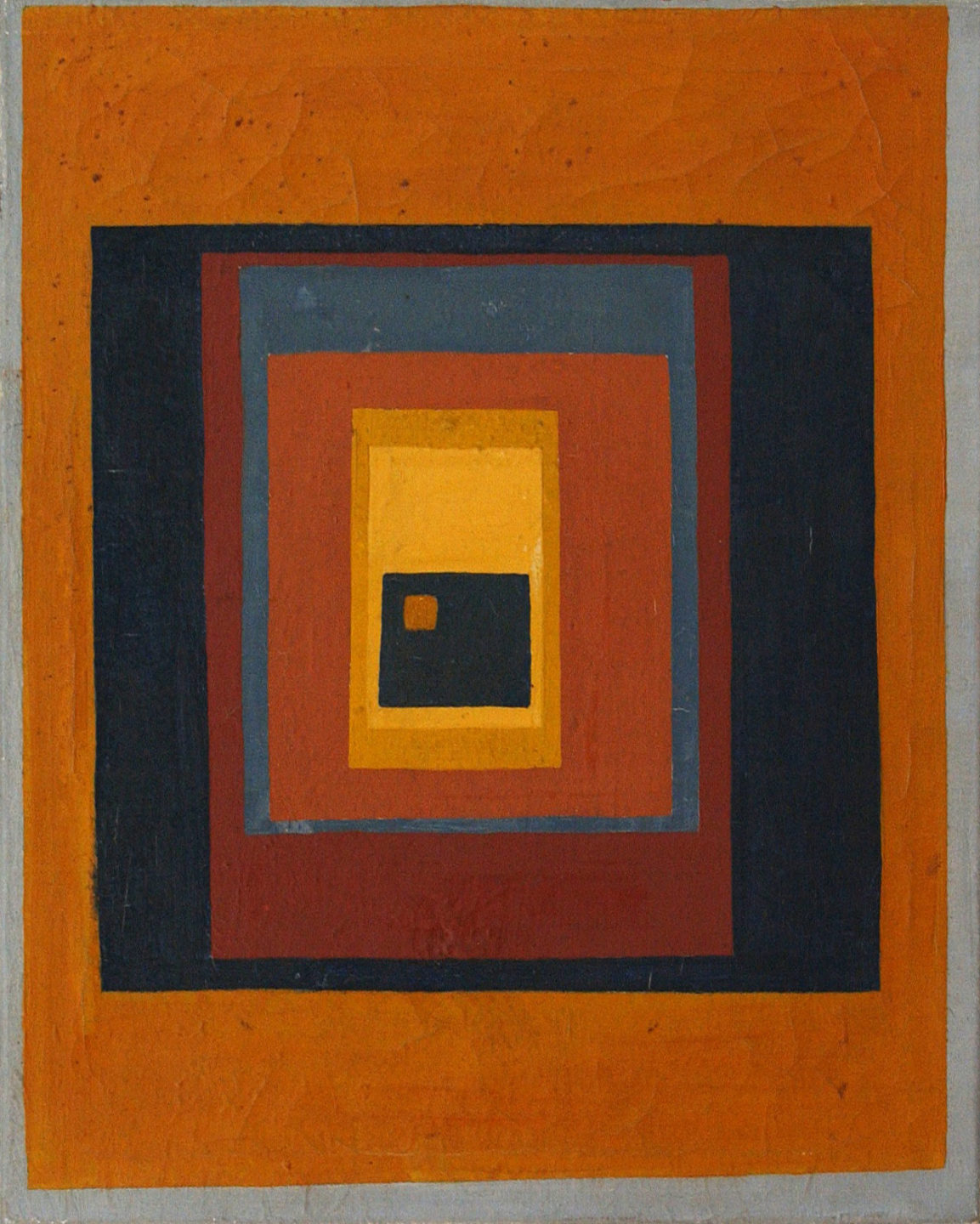

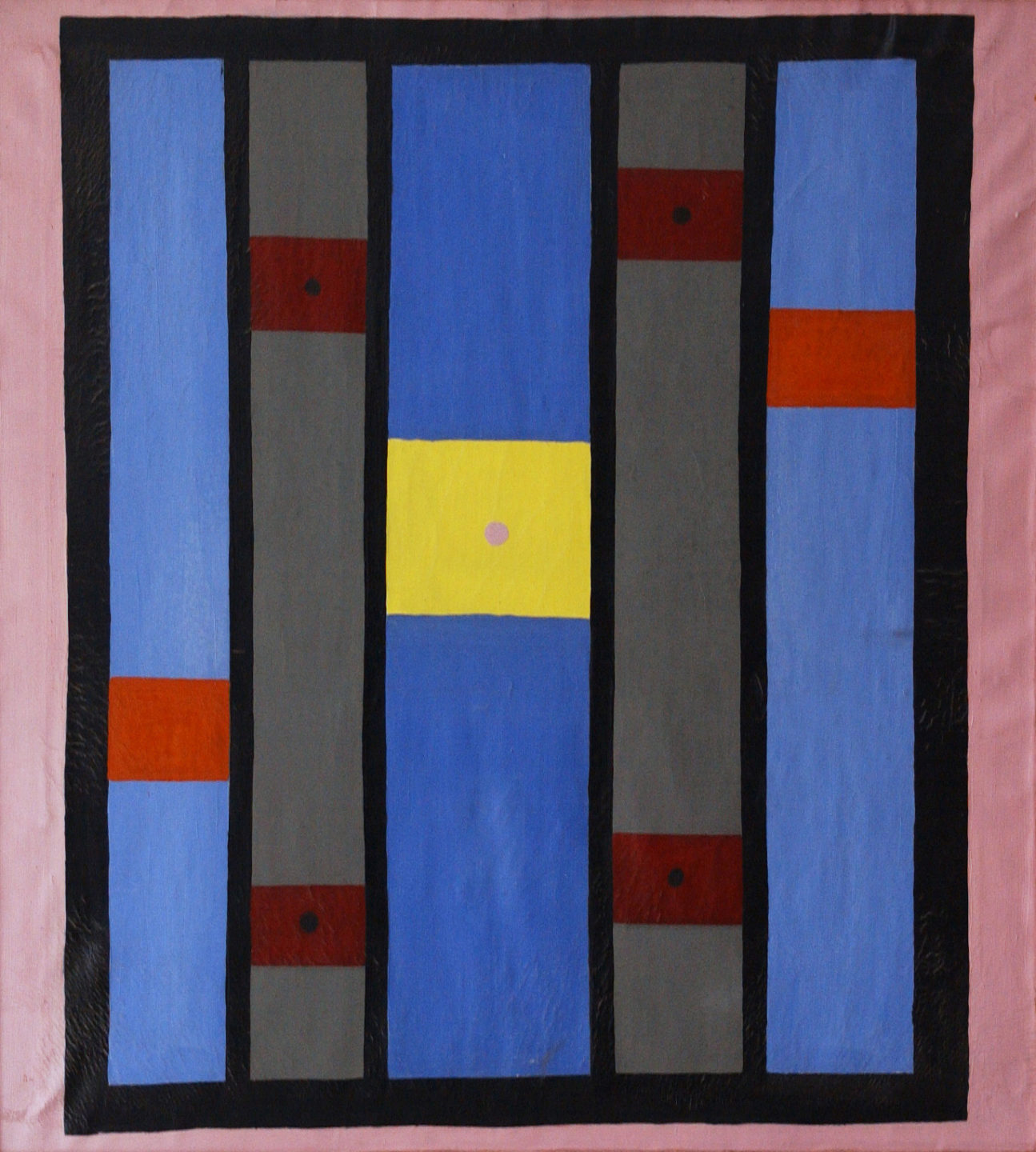

Stephen Willats, Architectural Exercise No.1, 1961

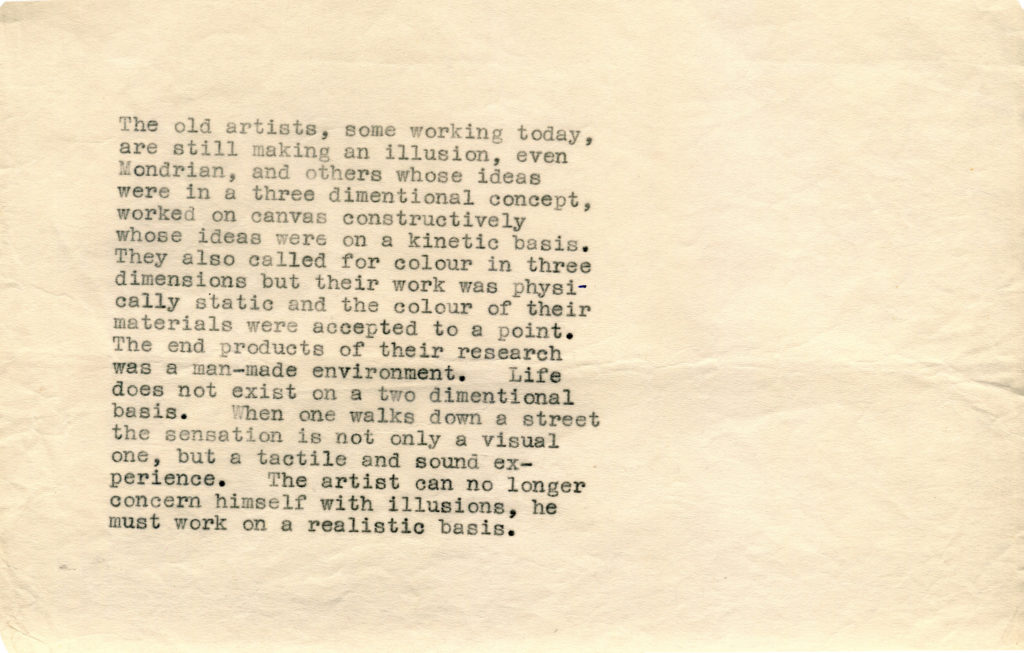

More info‘Life does not exist on a two dimensional basis. When one walks down a street the sensation is not only a visual one, but a tactile and sound experience…’ — Stephen Willats, 1961

Completed in 1961, the earliest work on view is one of the first to show Willats’ engagement with architecture. It is a response to – or a ‘deconstruction of’ as the artist puts it – one of the first residential tower blocks built in Notting Hill Gate, West London, near to where the artist worked (Willats’ Saturday job at the time was very close to the site, providing ample opportunity to survey the building’s progress). Also of influence were writings including Merleau-Ponty’s Phenomenology of Perception and discussions around modernism in international publications such as Art in America, Cimaise and Art d’Aujourd’hui, in which Willats was introduced to artists such as Josef Albers. ‘We were rebelling against this pictorial picture making and this figuration that came out of the English tradition,’ Willats recalls. ‘It was the start of something.’

It was also in 1961 that Willats began to write manifestos, copying these on to carbon paper and distributing them at exhibition openings. The manifesto reproduced below concludes with the lines ‘Life does not exist on a two dimensional basis. When one walks down a street the sensation is not only a visual one, but a tactile and sound experience.’

‘I was interested in the idea of the manifesto because it was a way of creating a territory or climate for your work to operate in,’ Willats says. ‘You issued it in advance of an action, that was the principle. The whole point of this manifesto was we were living in a dynamic situation and that the world is not two dimensional, that reality itself is made up of all different kinds of sensory component parts and we felt that all this should come together. We wanted to move away from this straitjacket of 1950s painting which constrained the artist within some sort of elitist situation. We wanted to break out of it. That was a common feeling.’

2

Oil on canvas

74 x 67 cm

29 1/8 x 26 3/8 in

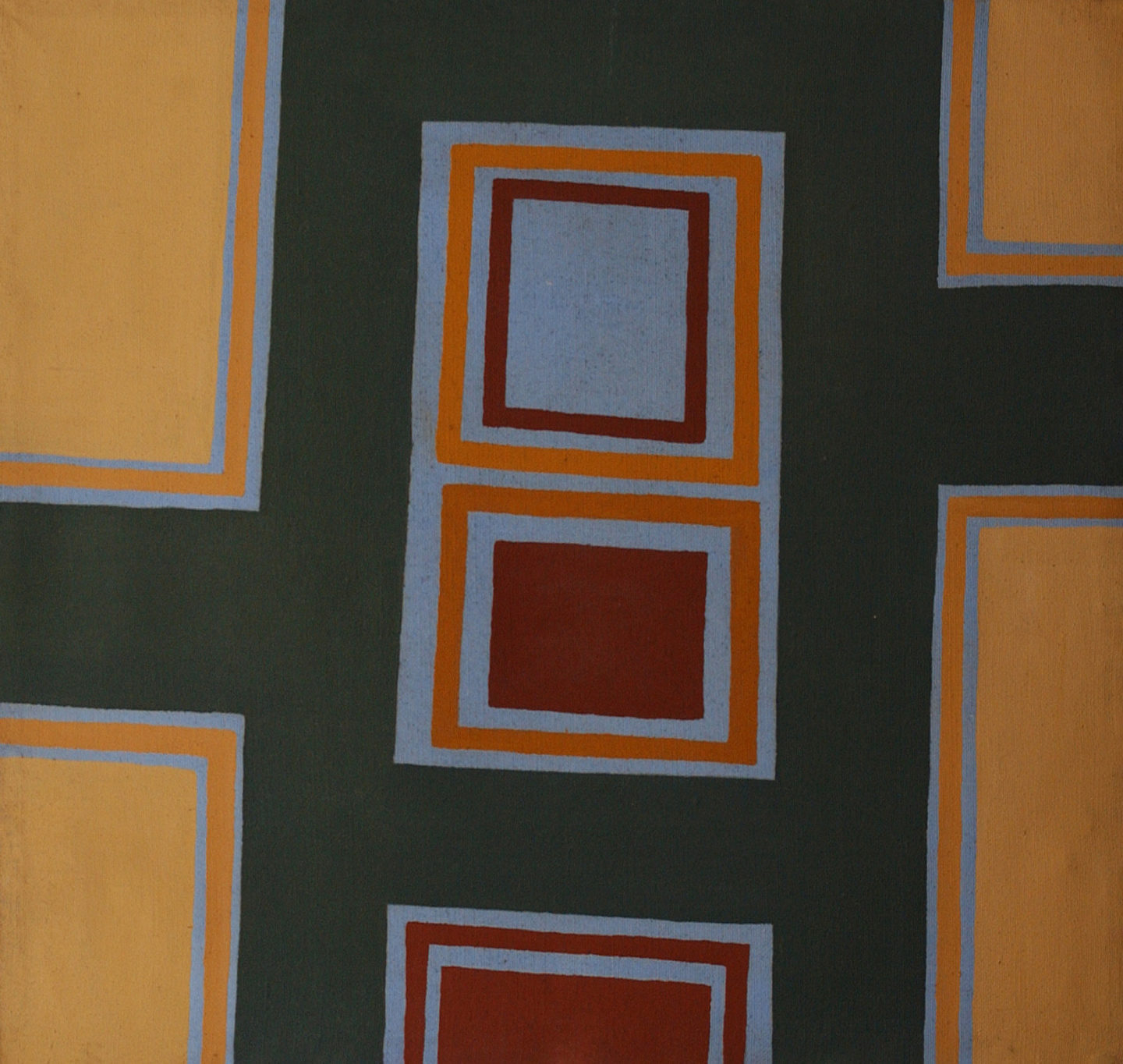

Stephen Willats, Architectural Exercise, 1962

More info‘I was fascinated by the idea that the window was this dynamic vehicle, this projection that you made into reality… It was like an encoding mechanism that made a picture.’ — Stephen Willats

In 1962, Willats started to attend the Groundcourse – a radical and influential experiment in art education at Ealing Art College which included exercises in which social processes were privileged over physical constructions, with students focusing on developing solutions to ‘problem situations’. For Willats this was a time of intensive production, and his work shifted further towards abstraction influenced by semiology, including writings by Merleau-Ponty and Marshall Mcluhan’s The Mechanical Bride, as well as theories on learning and language and their relationship to thought processes, social behaviour and class.

In Architectural Exercise, 1962, Willats continues his distillation of high-rise architecture – using the idea of the window, the lift and the building’s verticality while introducing new colours that signalled a deliberate break with the past. Speaking about this work, he comments, ‘I was fascinated by the idea that the window was this dynamic vehicle, this projection that you made into reality, but at the same time you were distant from it because you had the plane of the glass. It was like an encoding mechanism that made a picture. At another level I was also interested in the idea that the building itself was a kind of prison, that you could become entombed within it, and distant from reality, right up in the sky.’

2A

Oil on canvas

86.4 x 88.9 cm

34 1/8 x 35 in

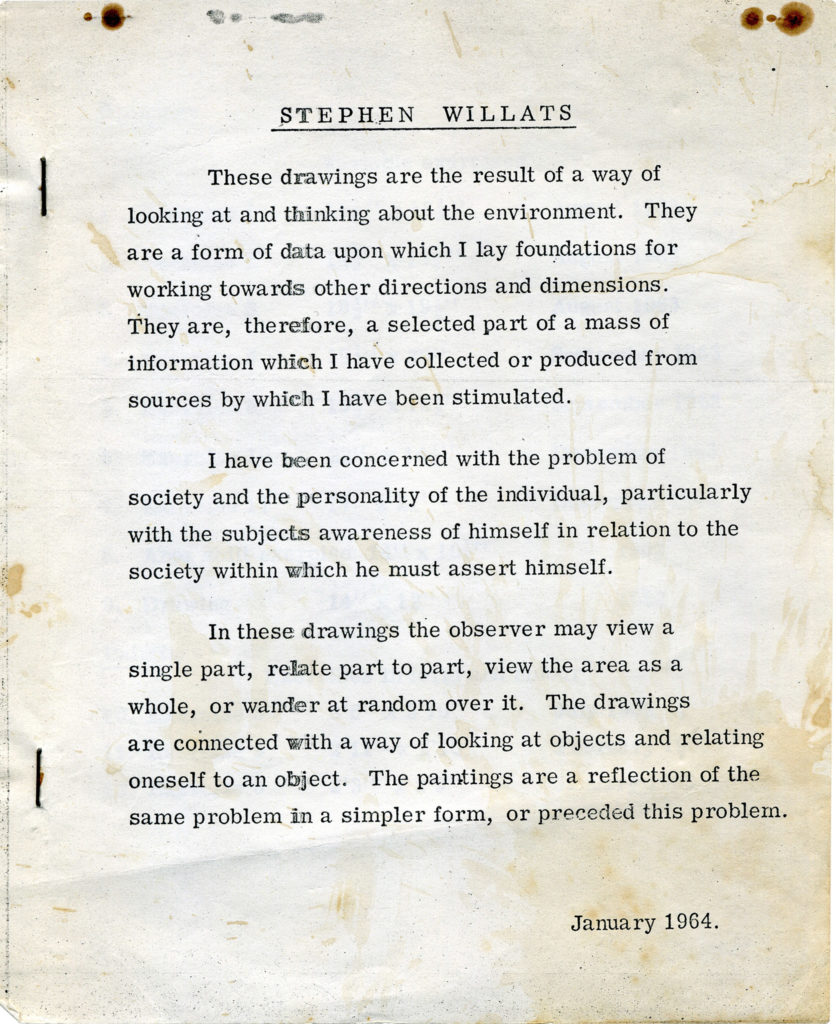

Stephen Willats, Exercise in Colour and Form No.9, February 1963

More infoExercise in Colour and Form No.9, 1963, continues Willats’ dematerialisation of the building, distilling it into an abstract structure using in this instance more muted colours. At the same time it introduces the important idea of connecting points – corridor or conduit like forms that reach to the left- and right-hand edges of the painting recalling the mid-twentieth-century idea of the walkway above street level.

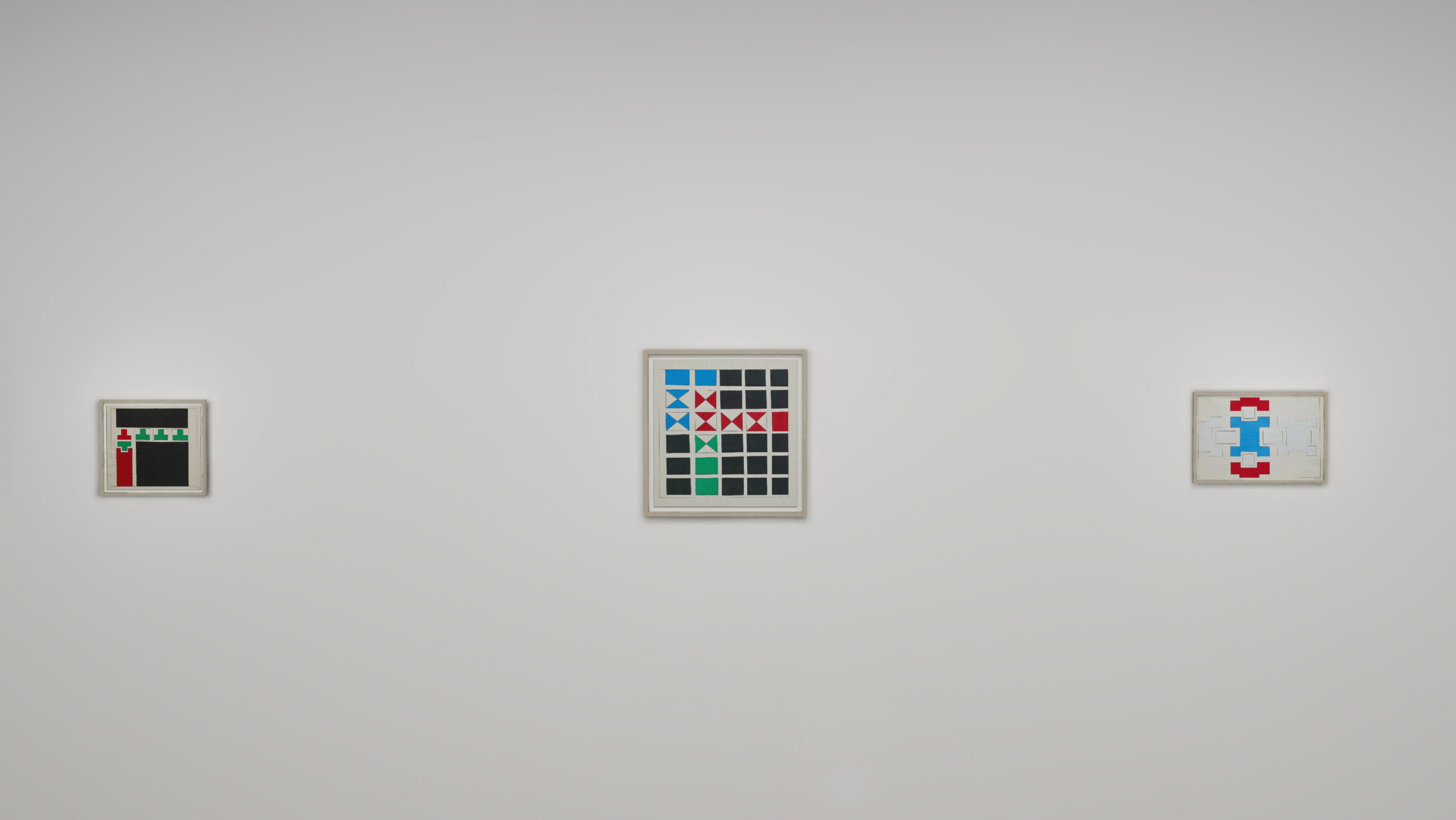

3

‘New things were coming up. We had the idea of chance, the acceptance of different philosophical areas, cybernetics was coming, systems theories, behavioural theories… the whole word was full of different things that weren’t there before, moving forward.’ — Stephen Willats

Works in this series, including Exercise in Colour and Form No.9, formed the core of Willats’ exhibition held in January 1964 at the Chester Beatty Research Institute, the pre-eminent national cancer research unit, in Chelsea. Set up in a common room at the Institute by a group of doctors, the exhibition space held a number of far-reaching exhibitions that ranged across various interrelated ideas and disciplines. At that time Willats had a studio in Radnor Walk, Chelsea, studying texts around ideas including the random variable, which is derived from probability theory (the mathematical model of uncertainty), as well as early computer science. Their interests aligned around systems – sociological and biological. In a text accompanying the exhibition, Willats wrote ‘I have been concerned with the problem of society and the personality of the individual, particularly with the subject’s awareness of himself in relation to the society within which he must assert himself.’

‘New things were coming up,’ says Willats. ‘We had the idea of chance, the acceptance of different philosophical areas, cybernetics was coming, systems theories, behavioural theories… the whole word was full of different things that weren’t there before, moving forward. Later, you had the idea of lateral thinking and that was incredibly interesting, and still is to this day, the idea of instead of accepting hierarchies of information, think of mosaics of information, think of moving sideways. In my own way I was embodying all these ideas in these paintings.’

Area Development Drawings

Gouache on paper

48.3 x 54.6 cm

19 1/8 x 21 1/2 in

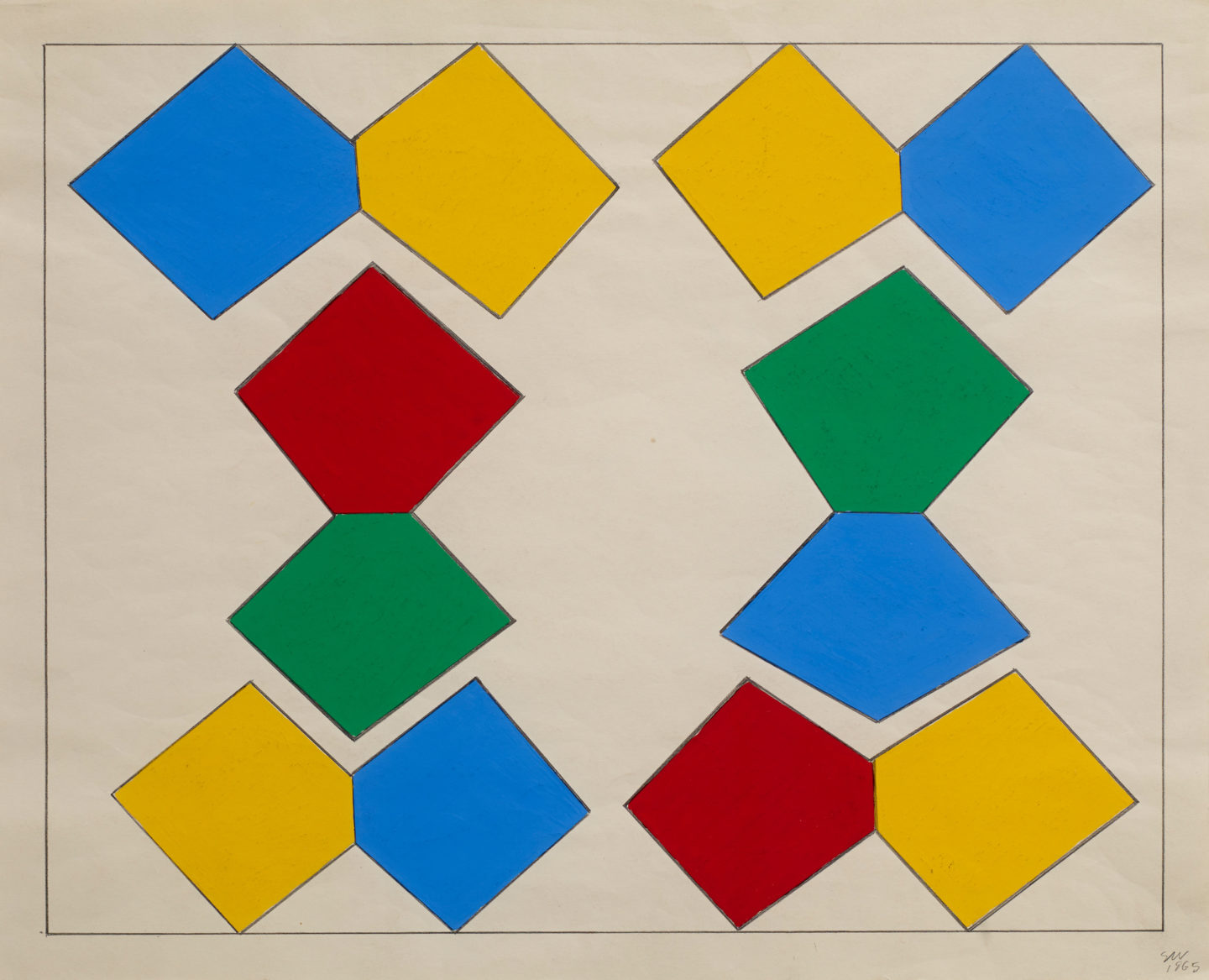

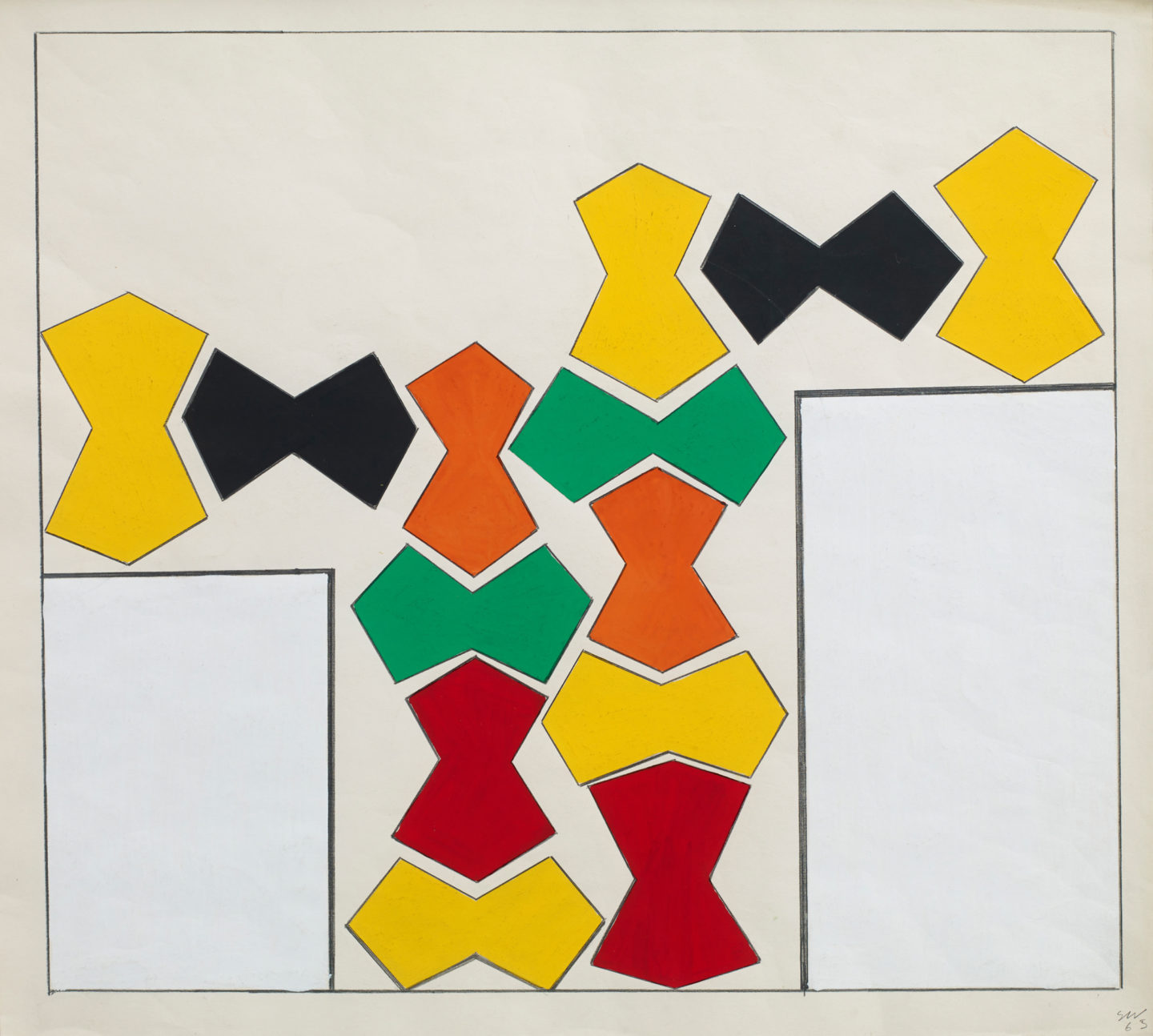

Stephen Willats, Area Development Drawing No 1A, 1965

More info‘What as a thought is internal, transient and unfocused, through the process of drawing becomes clear and possible; to be understood by someone else, from one person to another – a vehicle for social exchange’ — Stephen Willats

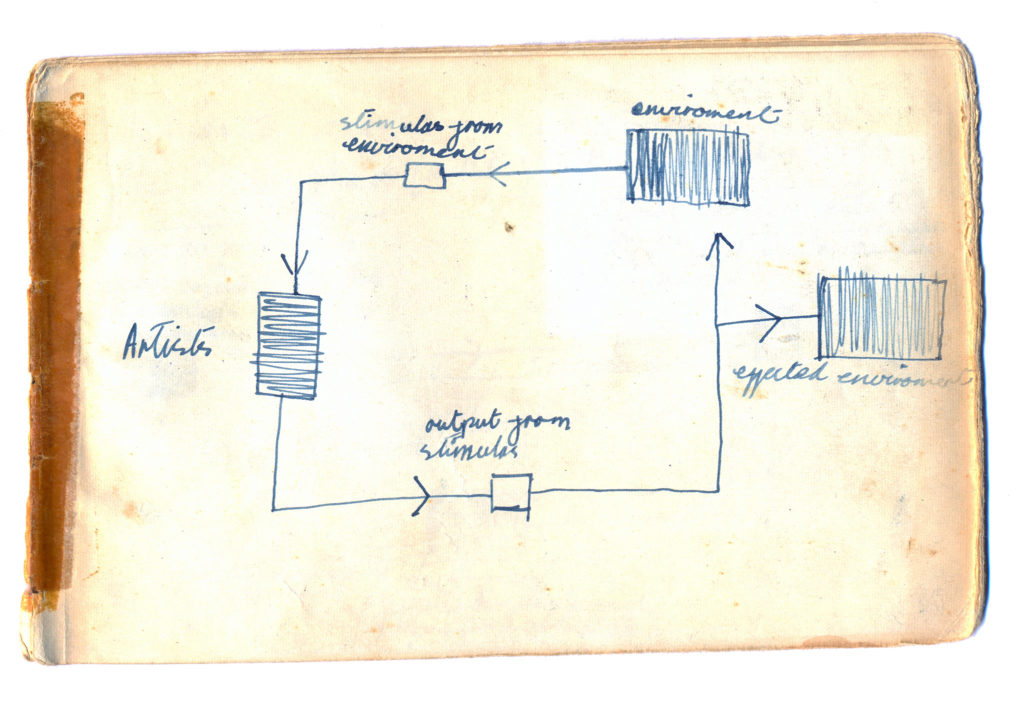

The act of drawing for Willats has since the 1960s existed on multiple levels, each related but with specific outcomes and there is a marked consistency in his approach to this throughout the six decades of his practice. Writing about the role of drawing, Willats explains, ‘What as a thought is internal, transient and unfocused, through the process of drawing becomes clear and possible; to be understood by someone else, from one person to another – a vehicle for social exchange. So the drawing can be both descriptive, in that it gives a view on something that already exists, or prescriptive, in that it seeks to represent something that does not yet exist, is only imagined as a possibility. Something only becomes a possibility once it exists as a thought.’

The Area Development Drawings are works in which Willats adopted the reduced language of diagrams to simplify complex correlations and to convey dynamic relationships within social networks. In Willats’ practice, diagrams do not serve as explanations, but rather as a way of seeing and changing ways of seeing. As speculative tools for mapping systems, they have the potential to describe social relationships and to offer new philosophical, social and ideological visions. He uses them to visualise and conceptualise our social reality, transforming in these early works constructivist geometries through his understanding of analytic models and the diagrammatic approaches of, among others, cybernetics and systems theory.

While by this point Willats had rejected modernism’s drive towards pure aesthetics in favour of documentation and research, in these works he nonetheless develops a vibrant visual style in part borne out of the urban culture of the 1960s.

5

‘It was a cross fertilisation of different disciplines, and seeing that they could help you in what you were doing.’ — Stephen Willats

In 1965, Willats was introduced to Dean Bradley, a Canadian graphic designer, who in turn introduced him to theoretical models in advertising (Bradley went on to co-design with Willats the first issue of Control Magazine, which is still published by Willats today, acting as a vehicle for proposals and explanations of art practice between artists seeking to create a meaningful engagement with contemporary society). Willats interest in the language of graphic design and advertising, along with theories about how colours and shapes motivate people and effect their reception of information, was galvanised later that year when he took desk space at Design Communications, a progressive advertising agency in Fitzrovia, at which Bradley worked. Many of the Area Development Drawings were developed in the febrile atmosphere of Design Communications, which Willats describes as ‘a hundred per-cent energy’.

‘It was to do with communication, reaching out, changing the way people saw things’, he says. ‘I didn’t want to follow [advertising theory] exactly because it was about a kind of determinism, to do with concepts such as product switch, but the Area Development Drawing series came out of being in that advertising space. It was a cross fertilisation of different disciplines, and seeing that they could help you in what you were doing, that they could aid where you wanted to go.’

6

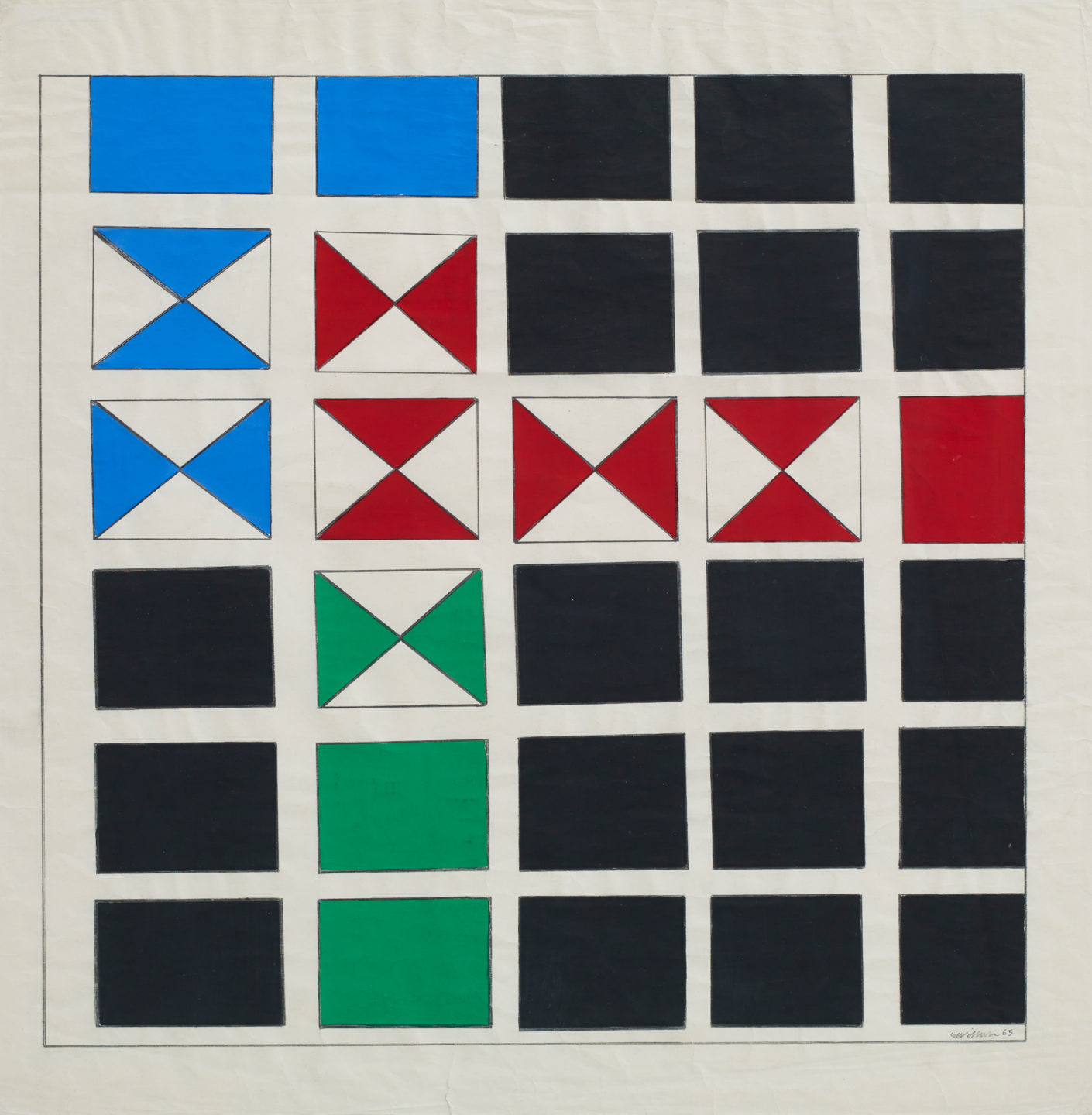

Gouache and pencil on paper

52.1 x 50.8 cm

20 1/2 x 20 in

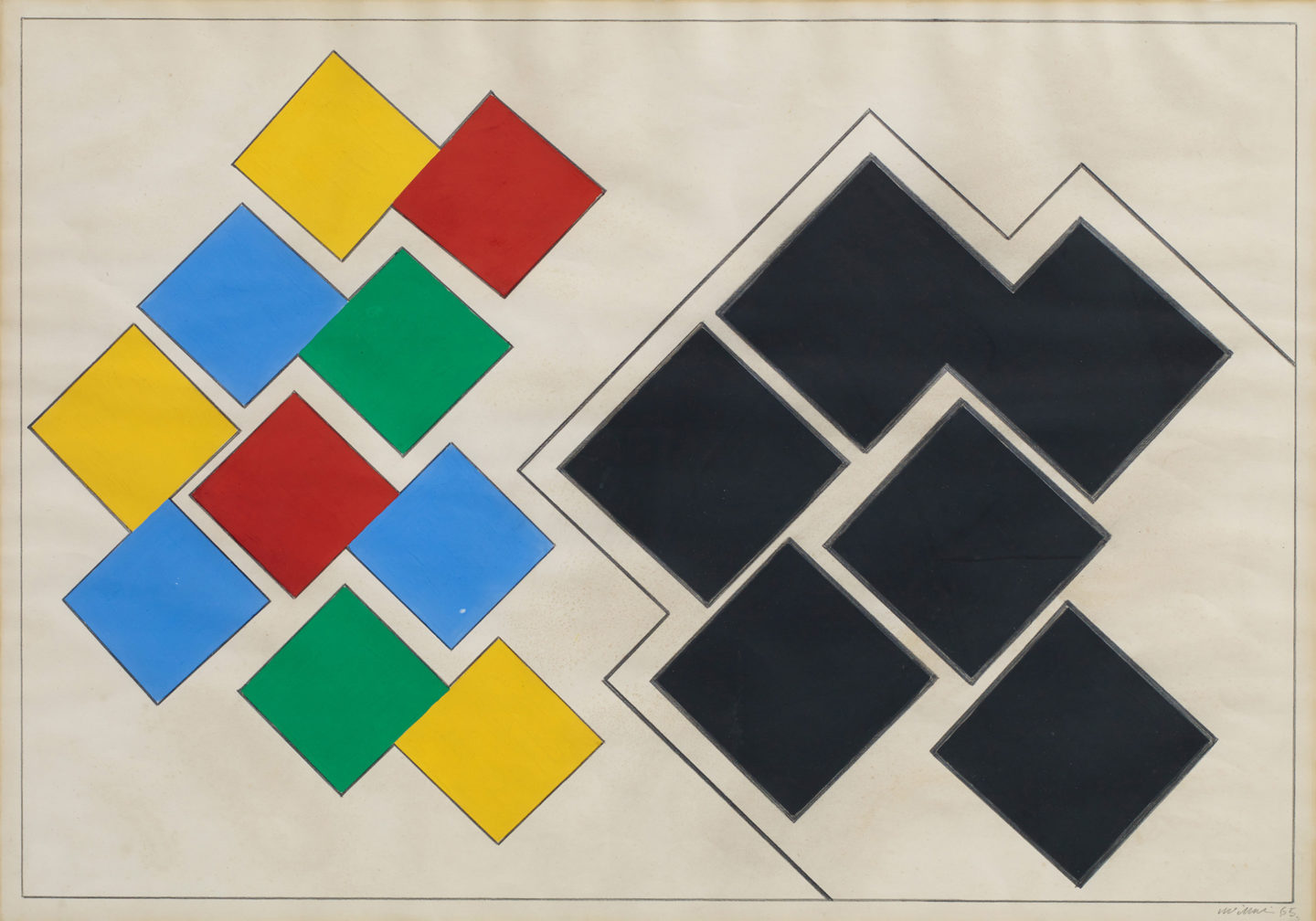

Stephen Willats, Change Exercise No. 13, 1965

More infoThe Change Exercise works were made at the same time as the Area Development Drawings and take into consideration the idea of dynamic systems. The work visualises cybernetic theories about movement and stability, as indicated by the spacing of the columns and rows of rectangles – in black, white, blue, red and green – within a larger pencilled square. Movement is implied by the placement of the rectangles, which look as if they are sliding towards the right into an invisible field beyond the frame, and also by the colours and patterns of the rectangles, which lead upwards and, again, to the right. These works form a connection with a number of two- and three-dimensional works from the period, including the Visual Transmitters, that explore multiple directions in systems, with variables changing from version to version, examined here in graphic form.

7

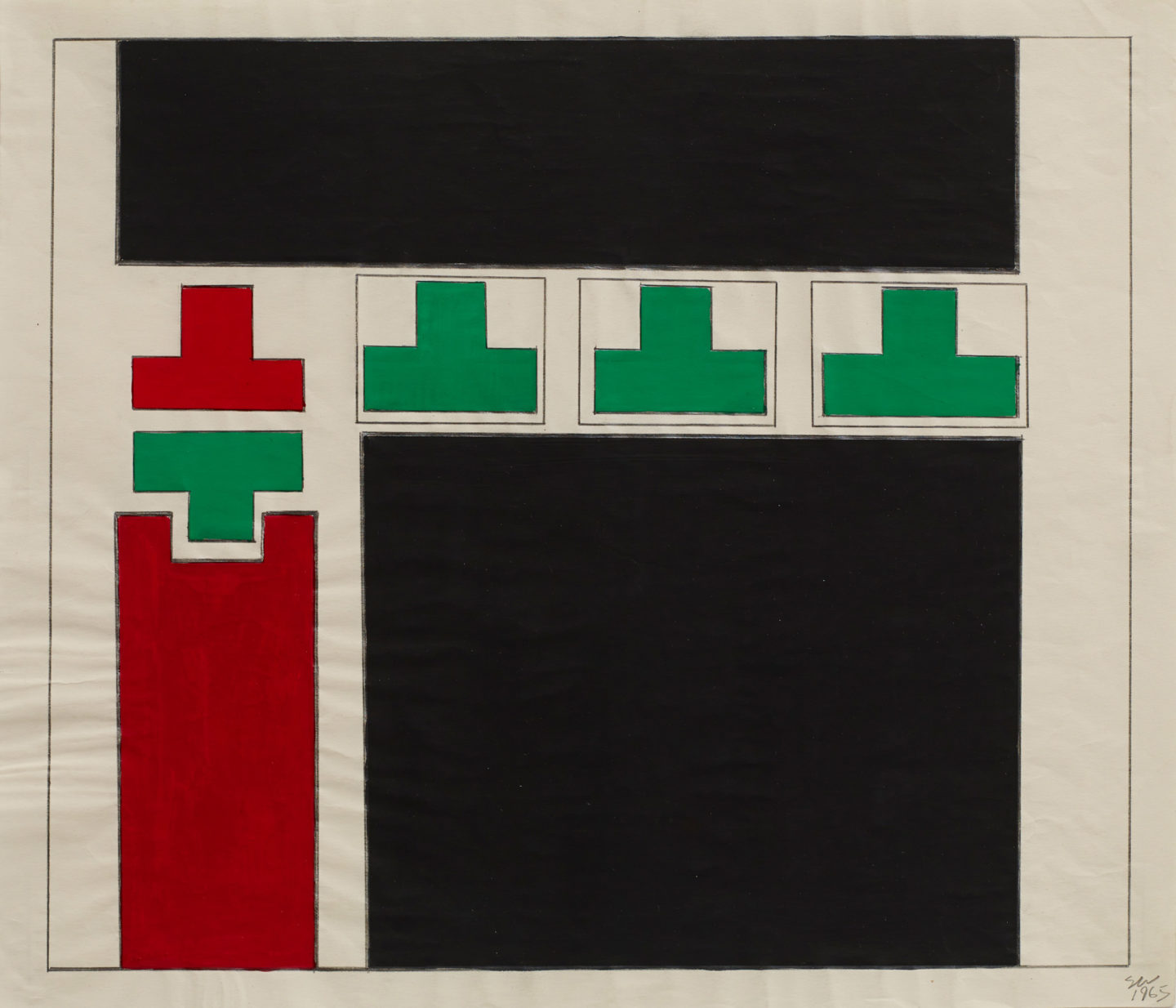

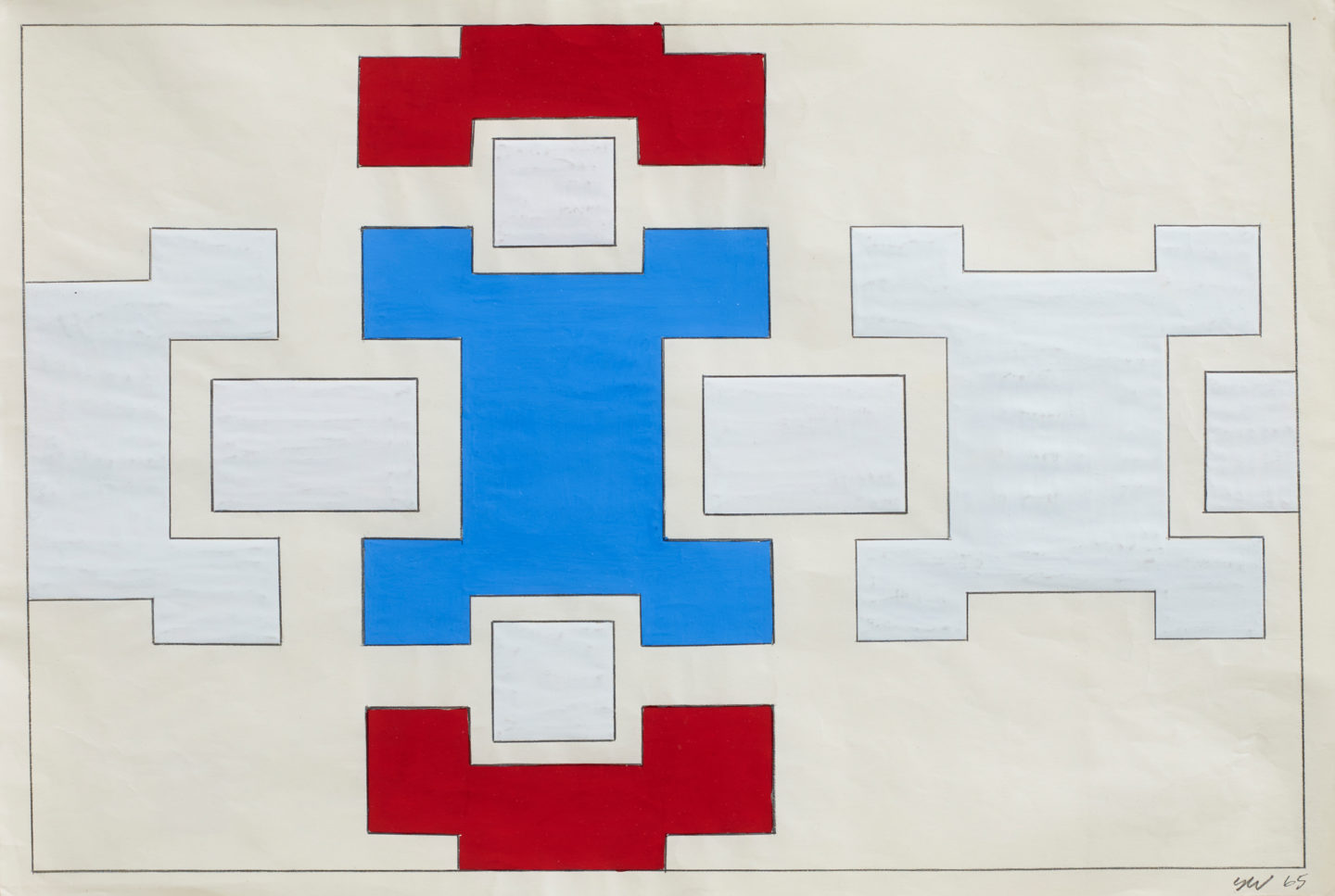

The Unit Drawings constitute a further examination of systems and structures, taking architectural plans and conceptualisations as a starting point and underlining Willats’ ongoing interest in constructivism during this period.

Writing about his work from this period, the artists notes, ‘I see the diagrammatic model as a catalyst for the representation of speculations of the possible and, since the early 1960s, the formal creation of a sequence of diagrammatic models has provided parameters to the evolving form of my subsequent art practice… I use the idea of the model as a reductive representation of an actual possible state (the world as it is and the world as it could be), in that it consists of fewer parts than that which it represents, so less is implying more… With a model, fewer parts than the original have to imply the complexity of the original. You can fill it in yourself, and this cognitive act of filling in is an active engagement with your existing frame of reference.’

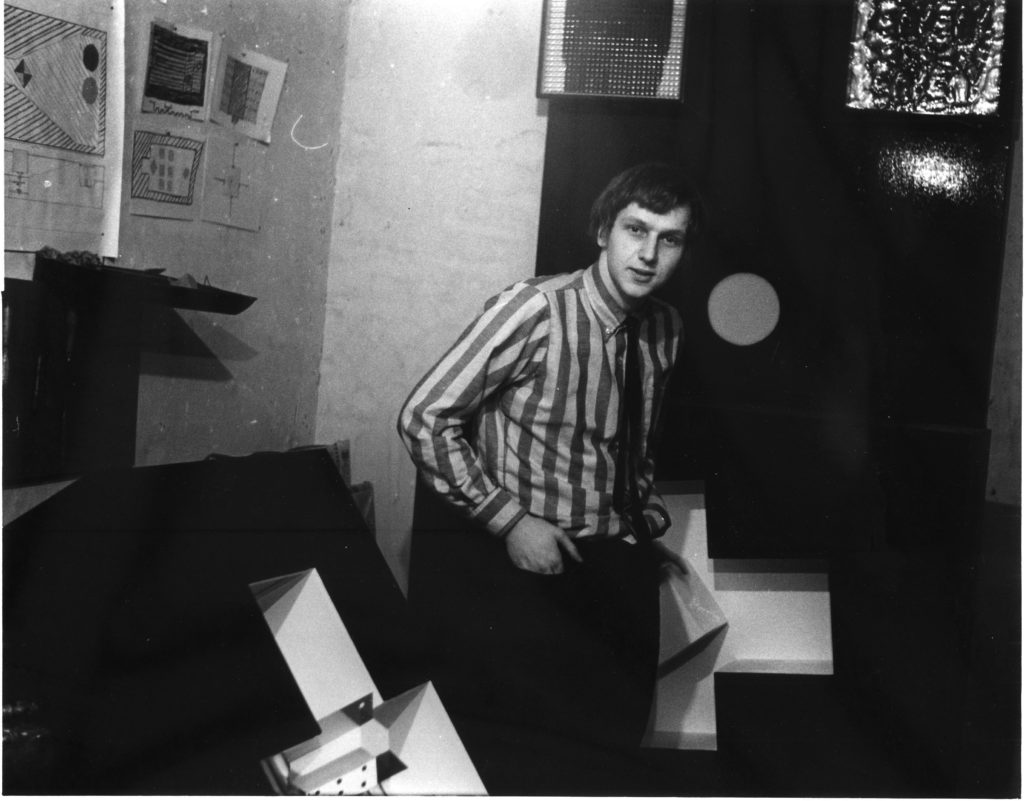

About the artist

Stephen Willats was born in 1943 in London, where he continues to live and work. Recent solo institutional exhibitions include Languages of Dissent at Migros Museum, Zürich (2019). His work has also recently been featured in the Chicago Architecture Biennial (2019–2020), Still Undead: Popular Culture in Britain Beyond the Bauhaus at Nottingham Contemporary (2019–2020), Pushing Paper: Contemporary Drawing from 1970 to Now at the British Museum (2019–2020), Objects of Wonder, British Sculpture 1950s–Present, featuring works from the Tate collection, at the PalaisPopulaire, Berlin (2019).

Previous solo exhibitions held at international institutions include: HUMAN RIGHT, mima, Middlesbrough (2017); THISWAY, INDEX, Stockholm (2016); Man from the 21st Century, Museo Tamayo Arte Contemporáneo, Mexico City (2014–2015); Concerning our Present Way of Living, Whitechapel Gallery, London (2014); Control: Work 1962-69, Raven Row, London (2014); Conscious – Unconscious, In and Out the Reality Check, Modern Art Oxford, Oxford (2013); Stephen Willats: Surfing with the Attractor, South London Gallery, London (2012); COUNTERCONSCIOUSNESS, Badischer Kunstverein, Karlsruhe, Germany (2010); Assumptions and Presumptions, Art on the Underground, London (2007); From my Mind to Your Mind, Milton Keynes Gallery, (2007); How the World is and How it could be, Museum für Gegenwartskunst, Siegen (2006); Changing Everything, South London Art Gallery, (1998); Buildings & People, Berlinische Galerie, Berlin, (1993); Meta Filter and Related Works, Tate Gallery London, (1982); Concerning Our Present Way of Living, Stedelijk van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven, (1980); 4 Inseln, in Berlin, National Gallery, Berlin, (1980); Concerning our Present Way of Living, Whitechapel Art Gallery, London, (1979).

In 1965 Willats founded the magazine Control, which is still in publication.

Further information on Stephen Willats

Vortic installation

In tandem with Art Basel OVR: Pioneers, the works have been installed on Vortic, the leading virtual and augmented reality platform for the art world.

Click here to view the presentation on Vortic

Vortic is available to view online at vortic.art, or by downloading for mobile and tablet devices from the App Store now.

Learn more about Vortic here.

For enquiries regarding featured works and other matters, please contact the below:

Victoria Miro: salesinfo@victoria-miro.com

Vortic: enquiries@vorticxr.com